published: 6 /

11 /

2019

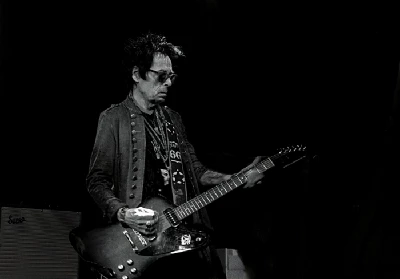

New York guitarist Earl Slick talks to Lisa Torem about performing with former Sex Pistol Glen Matlock, and his experiences working with David Bowie and John Lennon.

Article

Earl Slick’s signature stamp has graced the recordings of legends, such as the late David Bowie, with whom he played during the mid/late 1970s (‘Young Americans,’ ‘Station to Station,’), and continuing into the 1980s and in 2013, when he contributed blistering guitar sections to Bowie’s penultimate album, ‘The Next Day’.

Earl first worked with John Lennon during the early Bowie days, and again during the recording of the Jack Douglas produced ‘Double Fantasy’ album.

Currently, he is preparing to perform with songwriter/performer Glen Matlock (of Sex Pistols fame) and the Tough Cookies (also including Jim Lowe and Chris Must) at the 229 Club in London on August 10th.

In interview with Pennyblackmusic, Earl discusses his long-term friendship and current working relationship with Glen, the material on their upcoming set list, and his reactions to working with Bowie and Lennon.

PB: For your upcoming London gig, will you be basically drawing from Glen’s new ‘Good to Go’ album or classics from the Sex Pistols?

ES: What we’ve been doing is usually just a few Sex Pistols songs. Then we’re pulling from a variety of stuff that I’ve done with Glen and some of the stuff he’s done on his own. So we’re pulling from all over the place.

But mostly it’s Glen’s stuff, which is great because it’s good stuff and we love playing it. And the audience loves it, so they don’t seem to be disappointed if we don’t do a bunch of Sex Pistols stuff.

PB: Regarding studio recording, Glen has positive things to say about your use of slide and Ebo on choice tunes, for example, on ‘Hook in You’. Can you talk about your strategy for translating stories into these sounds?

ES: It’s funny, because the way Glen writes, it’s very suitable for me to stretch a little further and use Ebos and stuff. It works really well actually. What it doesn’t really sound like, if you talk about Glen Matlock and how you think about Glen Matlock, he’s way more than what people think he is. He’s a great songwriter. He is so good, live with an audience. They just love him; He knows how to do it. He’s so honest, because he’s just having a good time. And if we have a good time, they have a good time.

PB: People may categorise you, Earl, as a blues-rocker, and perhaps, Glen, as punk. You’re saying it’s so much more. Still, some may consider you polar opposites. What brought you two together musically?

ES: We were introduced by a mutual friend, Keanan Duffty, a British clothing designer who lives in New York. He was around in the Malcolm McLaren days. He started out like a lot of these guys did, infused in the music end. And Keanan went on to do great things. He actually designed the David Bowie line that went into Target in 2012. He designed for everybody. He did a run of Sex Pistols stuff for everybody.

So me and him were friends and he introduced me to Glen. We had a very, short-lived band called, Slinky Vagabond. Myself, Keanan, Glen and Clem Burke from Blondie. I knew Glen a very long time. We did some gigs in New York. With Glen being in London, me and Keanan in New York, and Clem in L.A., it just wasn’t feasible to get a whole lot done. But that’s how I met Glen. We hit it off and over the last couple of years I’ve spent so much time in the U.K. we just started doing these gigs together. It’s cool.

PB: Regarding select tracks, about ‘Sexy Beast,’ Glen says, “You peeled the solo off in one take.” Is that typical for you?

ES: My solos as a rule are one take because that’s the take that I’m not thinking. Second and third take, I’m thinking, and they suck. I always tell the producer or engineer, as soon as I pick my guitar up, start recording (Laughs).

PB: A lot of your ideas percolate in the subconscious?

ES: I might appear to just be noodling, but record it and make it a solo.

PB: You’ve got a 1968 Gibson J45, which appears to be one of your best friends. With all of the guitars you could record and tour with, what makes this guitar so unique?

ES: It’s a great guitar. I bought it new. I bought it in 1970 and I thought it was from 1970. But about four or five years ago, I was in this guitar store talking to the owner. He says, “It doesn’t sound right. I think it’s a different year.”

So I gave him the serial number and he tracked it and said it’s a 1968. I bought it new. Back then, it wasn’t like we had all of these guitar supermarkets. It was all mom and pop stores. Sometimes there’d be equipment, and it would sit there for a year until somebody bought it. So that was my first real acoustic guitar. And it’s a funny thing about that guitar. It has held up better than any of my other guitars, as far as acoustics go.

So when it comes to special projects, I bring it. I don’t bring it on the road ever and I never bring it anywhere where it’s left. I always bring it in my hand. On the way, while I’m there, and on the way home.

PB: Let’s talk about your work with David Bowie. You originally replaced guitarist Mick Ronson. When you got the call, you had very little time in which to learn repertoire. It was a tall order.

ES: To be honest, when I did the audition, I wasn’t terribly familiar with Bowie. The one Bowie album, I had, was ‘Aladdin Sane’. And the reason I bought that was, I heard ‘Panic in Detroit,’ and the first thing I thought was, “Wow, that’s Bo Diddley.” I loved the stuff that Mick did on the record. So I had that, but I didn’t have anything else. And when the audition came up through a friend of mine, what I ended up doing was borrowing some Bowie records from some friends. I got familiar with the basic style because album to album it’s always changing.

The only thing--I didn’t get nervous during the audition, I got nervous thinking, if I had to copy everything that Mick did, because I’m lousy at, I can’t copy things. I can sound like somebody if I put my mind to it, but I can’t copy. My brain is not wired for note to note to grab something.

David seriously let me off the hook. I asked him about it. He said, “I hired you. I like what you do, so just do what you do.”

PB: That’s interesting because another musician might prefer to do the note to note thing. So how else do you approach creating a solo? You’ve talked about not over-thinking…

ES: If I’m going to learn something, I’ll just play it, without even picking my guitar up for a couple of days. Then I pick my guitar up and just play along with it for a day or two. Then I get the essence of it, and everything else just kind of happens. My fingers just have a mind of their own at that point.

Now there are some signature lines that Mick did with DB. But they were easy to learn because they were structured. In ‘Starman,’ there’s a great line in that. Even, the little solo at the end, it’s the only one, but I didn’t even have to sit down and copy it. It was engrained in my memory from hearing it, so I just played it.

My biggest fright… I wasn’t that green when I got the gig, but, man, the press is going to ream me. Mick was very much the driving force to sculpting David’s sound. He wasn’t just a guitar player that was noodling. Mick really stamped that stuff with himself. And he put together a lot more of the arrangements and things than people even realised. He wasn’t just a guitar player; so I knew that from listening to everything.

At any rate, I got away with it. We did the first couple of shows. I didn’t get a beating from the press or the fans. It was all good.

PB: You played on the ‘Young Americans’ album: ‘Fame’ and ‘Across the Universe’. What was it like playing with John Lennon during those sessions as opposed to later?

ES: You’re going to love this part. I was so fucked up during those sessions that I don’t remember, which John thought was absolutely hysterical. Honest to a fault. I told him, “I don’t remember meeting you.” (Laughs)

Every once in a while, in the middle of a take, he goes, “Do you remember me now?” it’s kind of pathetic, but you know… So I don’t have any kind of clue, what it was like in ’75, but in 1980, working with him was not dissimilar to working with David. He wasn’t at all heavy handed about what you did. He just wanted you to do what you would do in the context of his songs, which makes your life really easy, because either I don’t take direction well or I don’t like being told what to do, but I do something a certain way and I kind of go in to record something, and my mindset is you hired me because you like what I do, so I’m going to do that.

PB: You don’t shy away from the dark material. Later on, when working on ‘The Next Day,’ you really went gangbusters on ‘Valentine’s Day…’ So what I’m hinting at, is that you’re expected to be more than a guitarist/arranger. You’re often asked to be a “think tank.”

ES: On that tune, in particular, and at some other periods of time, he would play me, just a shell of a song, and ask me to come up with something, and I would just keep throwing stuff at him.

“Ah, that’s it. You got it right there.” What we’d do, we’d take whatever idea I had and we’d develop it, which didn’t take that long because all of those guitar dubs only took a couple of hours, the whole thing.

PB: It sounds like, when you create something original, you draw from your earlier influences. You talked earlier about hearing Bo Diddley in ‘Panic in Detroit.’

ES: It depends. Sometimes I do. Like in ‘Valentine’s Day,’ I could hear it finished in my head. Some of it, like the rhythm parts, I knew cold. If you really listen to it, on a good stereo or headphones, you hear kind of a ‘Waterloo Sunset’ rhythm guitar in there. I even mentioned that to DB when we were knocking around. It has Kinks written on it. So I approached the rhythm guitar like that, the dark, bluesy leads. I don’t even know if we discussed it that much—it just kind of popped out.

PB: ‘Dirty Boys’ was another explosive arrangement from that same album that’s received critical acclaim. In the ‘80s, with Lennon, you were trading these soulful harmonic lines with guitarist Hugh McCracken. How involved were producer Jack Douglas and John Lennon himself with those arrangements?

ES: The one that stands out, we really loved it, man, was, ‘I’m Losing You.’ That was put together by John, Hughie and myself. What John did, he said, “Okay, there’s four lines in that thing. You, Slick, play the first, and Hughie, you come up with the idea for the second. Slick you come up with the third one, Hughie, whatever.”

We alternated. So I would come up with a line. Hughie came up with a line. We each had two lines in there. Then, what we did, once we decided, yeah, those were cool, we played them together. And then we harmonised them and then we, like, doubled and tripled them, not to get a big sound, but to get a specific texture.

PB: Now on ‘Just Like Starting Over,’ there’s a marked difference between the guitar on the verses and on the bridge. What’s the story behind constructing that dynamic?

ES: That’s just me playing what came naturally to me, because it had a 50’s thing, and I just went after it, that way. That developed within the first day of knocking the song around. It was one of the first things recorded, if not the first one.

PB: In regards to ‘Watching the Wheels,’ you shared co-writing credit with Andy Newmark, Hugh and Tony Levin. So how did that work?

ES: I did? Oh, cool. (Laughs) I don’t know. It’s funny. When you’re putting stuff together like that in the studio, it depends, how far it’s been developed, on how much you really contribute. You come in, and sometimes they have the whole thing together, other than the overdubbed licks; on some of them we have to piece it together. And you don’t normally get writing credit for something like that.

John and DB were always open to picking our brains. The reason that I liked working with them so much is that their approach was I got these guys in here. They do a specific thing that I like, so the best thing I can do is to actually get them to do what they do, as opposed to writing something out and dictating, note to note, what we should be playing, which actually is a much better way to do it because the essence of it is, they’ll get a much better, more natural sounding record than if they would bark out orders, “Play this note and play that.” Because in that case, you don’t need me. You need someone that reads music. You need a session guy. I’m not.

PB: There is circulating a stripped down version of ‘Double Fantasy’. What happens, when you’re a guy on that album and this other version comes out? Do you have any say in how those alternative versions come out? Does that mean some of your work might be buried in the mix, deleted, changed and perhaps not to your liking?

ES: You mean when they remix it? I was there for some of it. But it really wasn’t my place to interject anything. The people that were at the helm. Jack was there. They had it down. They knew what they were doing. I felt they were doing a good job anyway. I was just happy to be there and listen to it.

And I don’t get married to parts. So it was kind of cool to hear it cleared out of the overdubs. I like listening to my rhythm guitar recordings more than my solos. That’s what I enjoy doing more, just playing rhythm guitar. Solos are what they are, but the rhythm is what I really dig myself into.

The rhythm guitar is really the heart and soul of the song. That’s what makes the emotion. That’s what makes it move.

PB: You were involved in a project, ‘Diary of a Sideman’? What came of that?

ES: I did the Meltdown Festival with Yoko Ono in 2012 or 2013. It was the first and last time that we performed ‘Double Fantasy’ live. We had a bunch of different singers on there and there were a whole bunch of venues in this place. They offered me a room and I really didn’t know what to do with it and my manager suggested that we test out the book on people, so we put together a slide show and I did an hour-and-a half with Mark Adams, who runs all of the Bowie Social Media, and still does. And we went through the thing and it went really well.

There was a BBC documentary, producer/director named Frances Whaley there, and I had done one of the Bowie movies with him, “’Five Years’”. He said, “You know what? That’s a movie.” And we did make it into a movie for the BBC. It came out two years ago in July. It did great. I think you can find it. It floats around. It’s called ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Guns for Hire: The Story of the Sidemen#.

There’s another ‘Guns for Hire’ movie that has nothing to do with me. Mine’s way cooler because I’ve got Bernard Fowler in it, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood, Charlie Watts, all doing interviews. I got Steve Cropper, who let us into his house. I got everybody that I wanted, that really could drive the point home of what a sideman really is in the movie.

It really turned out well, and the Stones were so gracious to do interviews for it and they gave us some footage to use, as well. I narrate the film, I’m not continuously in the movie because I wanted it, not to be about me, I wanted it to be, this is what a sideman really is. You guys see it this way, but here’s the reality of it. And the movie did make the point.

PB: Guitarist Johnny Winter died in 2014. You showed up at Chicago’s Buddy Guy’s Legends for a musical tribute.

ES: That was weird, because I went there with a friend of mine from the Hall of Fame, Chris Stewart (former drummer of Genesis) and they bamboozled me into going to the Bowie Exhibit thing, which I’d already seen, and so I went with them and then we went over to Buddy’s.

Buddy’s out of town, but Edgar’s (Edgar Winter) playing. He played on one of my records years ago. So I went to say hi and Edgar invited me to play. And then Buddy walked in unannounced. We chatted for a minute. We hit it off and he invited me back. For a couple of years in a row, he invited me to do his residency. I’m going to do it again this year in January. I’ll probably play three or four nights. I sat in with him at B. B. King’s. Every time I show up, he drags me up on stage.

Oh, my God. This is ridiculous, because I remember seeing him when I was like eighteen years old, and have him blowing me away, and to have him walk in, when I was playing at his club of all places, and him being polite enough to invite me. I was like, “Wow. It doesn’t get any cooler than this shit, man. “

Buddy Fucking Guy inviting me to play with him at his club.

PB: What’s left? You’ve played with everybody. They want your unique sound. They can’t imitate it. I’ve heard you say you’d like to play with Keith Richards. Can you call him up and say, “Let’s do it?”

ES: You know, that’s not so easy. I love Ronnie. I know Ronnie pretty good. When I’m in London, he pops in occasionally. But right now, the thing with Glen is great. It’s good. It’s really low pressure. Everybody gets along. We have a really good time. And it gives me the opportunity to spend more time in the UK. My sights are pretty much set on working as much as I can out of the UK. because here things are just not the same as they are over there.

Every time I go to Chicago, it’s great. It’s funny, because I get a better reception there than I get in my hometown of New York, but then again it doesn’t hurt that you got introduced to Chicago through Buddy Guy.

But Chicago’s always been a really good touring town ever since I started playing. And some of the places that were like that. They’re not like that anymore. Chicago still has that. I’ve played there. Besides working with Buddy over there, I’ve done stuff with Chicago Music Exchange, Reverb.

I did do the Bowie Band tour this year and last year. We hit Chicago both times and both times it was great. I don’t think I’ve ever done a bad show in Chicago. I flew in for Buddy’s birthday. Dave Grohl was playing. It was raining like hell. And at the last minute they booked a theatre. It was a way smaller gig but he did it anyway and the audience was killer.

In the UK, all the musicians still network and hang out with each other, even if there’s nothing to gain other than having a cup of coffee and hanging out with the guys, which doesn’t happen so much here, but then again Britain is so much smaller. And it is concentrated around London, whereas we have Nashville, Austin. We got New York, we got Chicago. It’s not just one area.

PB: What was it like playing at the Cavern in Liverpool with Glen recently?

ES: That’s like a family situation now. I’ve been there so many times. They gave me my brick in the wall last time I was there. Me and Glen got our brick in the wall. You know, the bricks outside the building with all of the names on it? To get one of those bricks, you have to have played there. They put your name on the brick and it goes on the wall. And mine’s right next to Mick Ronson’s, which is cool. They moved somebody, because I said, “You know what? Mick’s brick is right at the entrance of the restaurant that’s across the street on that wall. “

And I said, “You know what? Right at the door is Mick. I want to be next to Mick.” I don’t know who was next to him, but he was moved somewhere else. (Laughs)

PB: Imagine you’re a super hero. What’s your power?

ES: Oh, God. Wow. Hmm. I know what. I would transport myself like ‘Star Trek’ so instead of flying everywhere and everything they’d just beam me to the next gig. I would just materialise at sound check. As soon as the gig’s over, I materialise in the hotel in the next city. That would be it. No airports. No stinky tour buses. Here I am. I’m at the gig. I’m at sound check. Alright, we’re out. Beam me up.

PB: Is there anything else you’d like to add about performing with Glen?

ES: We don’t plan anything too far into the future, which is good. I don’t mind that. It gives you more freedom that way, just in case something comes up, I don’t end up with a train wreck with my schedule where I double-book myself.

Working with Glen allows me the freedom to do what I’m going to do and also allows me and Glen to go out and do what we do. It’s perfect.

PB: Thank you.

Photos by Andrew Twambley

www.twambley.com

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earl_Sli

https://www.facebook.com/EarlSlickOffi

https://twitter.com/realearlslick

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-