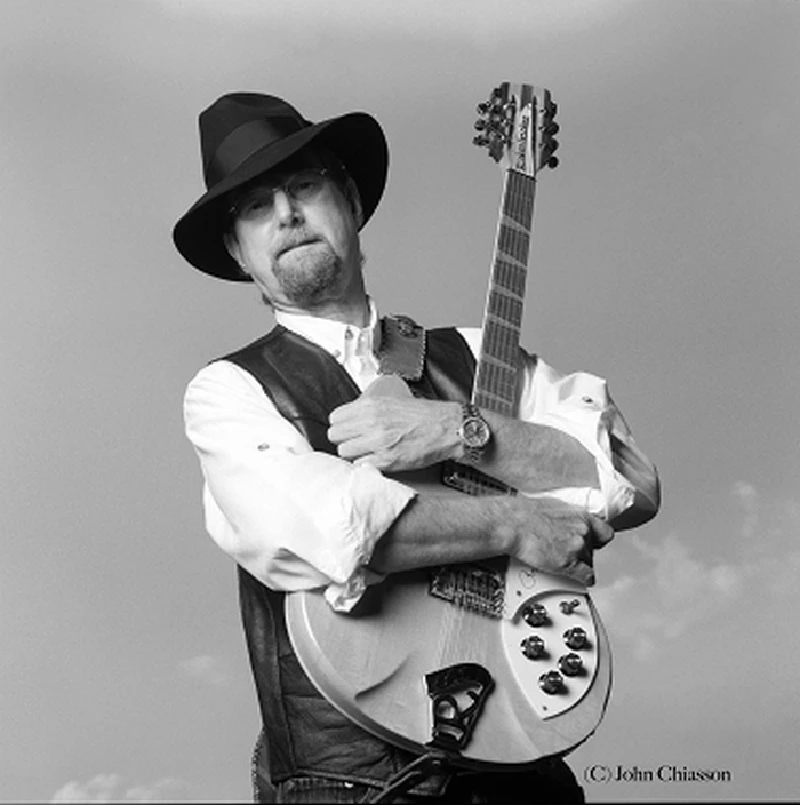

Roger Mcguinn - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 9 / 7 / 2014

intro

Lisa Torem speaks to former Byrds singer and guitarist Roger McGuinn about his personal influences, the importance of traditional muisc and his forthcoming UK tour

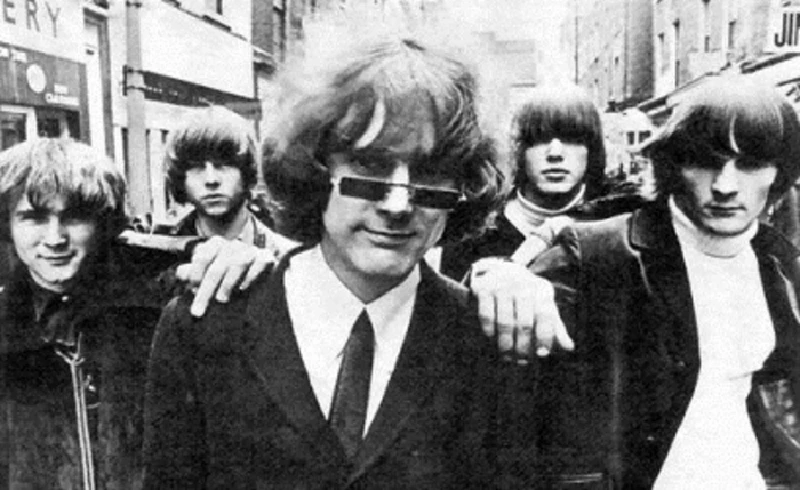

Native Chicagoan, Roger McGuinn, is best known for his role as lead vocalist and guitarist in the influential 1960's band, the Byrds. Prior to forming the Byrds in Los Angeles with Gene Clark in 1964, McGuinn’s earlier career included working with the Limeliters and with the Chad Mitchell Trio. He also worked with American singer, Bobby Darin, as a Brill Building songwriter and sideman. In 1963, McGuinn’s exposure to the Beatles inspired him to fuse his banjo picking style, which he had learned from Chicago’s Old Town School, with a “Beatles” beat. His appreciation for saxophonist, John Coltrane, also became integrated into this new sound. The 1966 song by the Byrds, ‘Eight Miles High,’ is one example. McGuinn also derived new sounds from the Rickenbacker, to which he would often use a compressor. Bob Dylan was also a huge influence, as was the material of Pete Seeger - The Byrds recorded Bob Dylan's ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and Seeger’s ‘Turn!Turn!Turn!' and topped the charts. 1968’s 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo' with guitarist Clarence White, Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman, is now considered by many to be the quintessential, country-rock album, although at the time of its release its diverse musical direction was questioned. The original line-up of the Byrds included David Crosby, Gene Clark, Michael Clarke and Chris Hillman, although during their existence, from 1964-1973, 1989-1991 and then in 2000, they went through a series of personnel changes, with McGuinn consistently being the stabilising force. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and the Flying Burrito Brothers were two examples of offshoots for the line-up. In the 1970s, McGuinn began a strong solo career, which included touring with Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue and forming McGuinn, Clark and Hillman. His 1991 'Back From Rio' album was a collaboration with Tom Petty. In the mid 1990s, McGuinn began putting a folk song each month on his Folk Den website, which became 'Treasures from the Folk Den', for which he received a Grammy nomination in 2002 in the Best Traditional Folk category. In 2005, McGuinn organizsd one hundred songs and formed a four-CD box set, which includes his work with the likes of Judy Collins, Odetta, Tommy Makem and many more iconic artists. In the autumn, McGuinn will bring his brand of original arrangements to the UK, where he will tour in support of his current recording projects. In this interview with Pennyblackmusic, McGuinn spoke positively about his unique guitar style, the artists who served as his personal influences, his adventures with Darin and Dylan and the importance of honouring and keeping alive traditional music. PB: You grew up in the Chicago area. What was it like studying with Frank Hamilton at the Old Town School? RM: It was a great experience. What happened was that I was going to the Latin School of Chicago, and my music teacher invited Bob Gibson to come over and play a set for us and I’d never heard that kind of music before. I’d heard rock and roll – I was into Elvis Presley and rockabilly. So, Bob Gibson came over with a five-string long neck banjo and did a lot of intricate picking and told stories, and I liked the material he was doing. I asked my music teacher what it was, and she explained to me that it was folk music. I’d heard the Weavers and Burl Ives on the radio, but I hadn’t paid much attention to it. She said, "If you’re interested there’s a school that’s opened up." This was 1957, and she pointed me over to the Old Town School. I went there and I had taught myself how to play a little bit, so I started with Frank Hamilton in the intermediate class and I stayed there until 1960 when he said, "You know, I can’t really teach you much more in this format. I can give you private lessons," but at that point I didn’t have the money for private lessons. So, I kind of graduated (Laughs) and went out on the road with the Limeliters. I remember going there two days a week, I think it was Wednesday nights and Saturday afternoons and spending two or three hours every time. Frank was really an excellent teacher. He was very patient. He taught me how to fingerpick and play the banjo and the twelve-string and all of these different styles of music, which were part of the curriculum there and Frank was really kind of the engine that drove that thing. Win Stracke was there too, but he was just kind of along for the ride. Dawn Greening, Frank Hamilton and Win Stracke started the school, but Frank was pretty much the whole engine. PB: The Gate of Horn must have held some good memories for you. RM: Yes, it did. It was a great club. Albert Grossman and Alan Ribback started it. There was omething that Grossman had run into in Paris. He had been fascinated by a cabaret that had a separate bar from a listening room, and that was something that hadn’t been tried in Chicago. It was either a coffee house environment or the bar was part of the listening room, where people talked and talked, and so he bought the Gate of Horn on that premise and it was a great, little club. I forget how many people it held. PB: I believe the club seated about a hundred people. RM: Yes, probably about a hundred people. I remember going there and watching the Clancy Brothers, Tommy Makem and Judy Collins. I didn’t see Joan Baez there. I think she was around at that time, but Bob Gibson played there a lot and so did Josh White. You could sit right up there next to the stage. I remember sitting three or four feet away from Josh White while he was playing, and it was an incredible experience. If you’d seen Josh White a few times, you’d know that he did a trick. He’d purposely break a string, and then while he was changing it he’d sing an a capella song. PB: What did you think of the film 'Inside Llewyn Davis'? Some say it cast a dark shadow on the folk music scene. RM: I haven’t seen the movie. I’ve seen the trailers for it. It looks like he’s kind of a loser. I think it was loosely based on Dave Von Ronk. Dave was leader of the hootenannies at The Gas Light Club in the Village. He was an active folk singer. I don’t think it was a dark scene in those days. but I haven’t seen the movie so I can’t say. PB; You developed a strong working relationship with singer Bobby Darin. How did that come about? RM: Bobby was interested in doing folk music in his show. He’d come up with the teenybopper ‘Splish Splash’ and then gotten into ‘Mack The Knife’ with a Frank Sinatra presentation, but somewhere along the line he fell in love with folk music and that’s why he hired me to back him up on the 12-string and play harmony behind him. He often had a bass and sort of a combo in the background and I would slide up next to him. What I learned from him wasn’t so much music as how to work in show business, the whole structure of show business and what to do. I would ask him questions about how to make it in show business. You have to really be on time, be in tune and you have to have a 360 vision where you see everything that’s going on around you. Those were all things that he taught me, and then he said, "Get into rock and roll." So, he was kind of the steering force that got me to edge out of folk music and into rock and roll, which was how I started – I started in rock and roll and I’d gone into folk, and I completely ignored rock and roll for several years. He said, "If you get into rock and roll, if you get a hit under your own name in rock and roll, you can do anything." You can be a movie star or whatever you want. It was his formula and it worked fine for him. PB: He had even asked you to act in one of his films. RM: He wrote a film and he wanted me to play the lead character, but the lead character was a junkie (Laughs) and I didn’t really want to do it. I left it up to the day that he had planned on shooting and he had a film crew out there and I said, "Bobby, I just can’t do this. I’ll pay you back for your expenses for the film crew and everything, but I really don’t want to play a junkie." So, he let me out of it, but he was pretty disappointed because I had told him I wanted to be in the movies and so he constructed this whole movie. But he thought I was a junkie. I really wasn’t. I wasn’t shooting heroin or doing anything like that, but he always suspected that I was. I remember one time at a recording session he wouldn’t let me leave the room. He wouldn’t let me leave the studio even to go to the bathroom or anything because he wanted to see me go through withdrawals, and, of course, I didn’t because I wasn’t doing that. PB: Paul McCartney was asked about how the Byrds had influenced the Beatles. He said, “The Beatles took that jangly thing…” Some people feel that the Byrds were a composite of the best of Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Is that how you would describe their early incarnation? RM: What happened is that I heard the folk music chord changes in the Beatles, in their early stuff, ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and ‘She Loves You’. Their very early hits had folk music passing chords in them. In other words, they wouldn’t just go from G to C to D. They would go from G to D minor to E minor to C and then A minor to D. Those are folk music chords and I went, "Wow." This is what gave me the whole idea of taking a folk song and putting a rock beat to it, so the Beatles inspired that whole thing but also the Rickenbacker twelve-string was something that George played in 'A Hard Day’s Night’. He didn’t do it exactly the way I did it because I played sort of a rolling pattern like a five-string banjo – I put an Earl Scruggs picking style onto the twelve-string that George wasn’t doing. His playing was mostly just plectrum style – single notes and chords. He was doing a lot of barre chords though. In fact, all the Beatles really didn’t use open chords like folk musicians. They used a lot of barre chords, which gave them the ability to play in any key. They could just as easily play in A flat as they could in G, which wasn’t true in folk music. You had to put a capo on and play it in the G position up the neck. So, the Beatles didn’t really have that jangly thing. But in Paul’s writing you probably did because you could hear that influence in other songs like ‘When the Rain Comes’ – you can hear the Byrds influence in that song and ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’. We were obviously interested in the Beatles, and then we sent it back across the Atlantic. I think the most positive example is in ‘If I Needed Someone,’ which inspired Derek Taylor to come over to my house in California and he said, "George wants you to know that he wrote this whole song based on a lick you did on 'The Bells of Rhymney'," which was, obviously, a Pete Seeger song. So that was definitely the Byrds influencing the Beatles. That was a great honour. PB: Looking back at the early photos, you all looked so British. Did the fans ever mistake you for British? RM: We were obviously patterning ourselves after the Beatles with our long hair and suits and ties. There’s a funny story about that. We got black suits with velvet collars. We used to wear them to Ciro’s, a Hollywood club. We left them in the dressing room and went home with our T-shirts and jeans. We went back the next day to put our suits on and do five shows. That worked out everyday but one day we went to Ciro’s and the suits were gone. I told John Lennon about that and he said, "I wish they’d stolen our suits." PB: Let’s move on to a later phase when you and Clarence White were doing dual guitar. Nashville reacted in a very hostile way when you first played your country tunes there. RM: Nashville didn’t receive us with open arms. We were sincerely into country music and we weren’t trying to make fun of them or do anything wrong. There was a political divide because there was the North and South, and the Right and Left politics got involved. We were in the wrong place at the right time to be in Nashville. We loved Nashville. We loved country music. We loved Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton and the influence of George Jones. It was the kind of music we loved. They didn’t perceive that from us. They thought we were just a bunch of long-haired hippies just trying to invade their territory. That was the reception we got. PB: 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo' had several Dylan covers and a cover of ‘Pretty Boy Floyd’ by Woody Guthrie. It essentially covered a lot of range and ended up becoming highly acclaimed. Given your initial reception, was it worth it? RM: It was definitely worth it because, as you say, if you look at the 'Rolling Stone' list of top 500 albums, 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo' is the highest ranking Byrds album – I think there are three in that 500, so people like it now. It was a political thing on both sides. The rock fans thought we had betrayed them by playing country. They thought we’d gone to the right wing. The people in Nashville thought we were a bunch of hippies invading their territory. It lost on both counts. It sort of fell through the cracks but as people listened to the album for its music as opposed to the political value of it, which evaporated over time, they liked the music, so it’s the most highly appreciated Byrds album now. PB: Let’s talk about your more recent projects. For example, The Folk Den Project. ‘Wagoner’s Lad’, Joan Baez, ‘Alabama Bound,’ Pete Seeger, some beautiful ballads with Judy Collins, the fiddle playing of Eliza Carthy. What have been some of the highlights? RM: I was a big fan of Joan Baez when she came out. She’s a year older than I, so we’re both contemporaries. I met her back in the 60’s at Club 47 in Cambridge, when I had started working with the Chad Mitchell Trio in the autumn of 1960. She was unknown at that time except locally in Cambridge. So, I went to see her and got to talk to her. I was smitten by her. I thought she was great. She could sing beautifully and she finger picked, which was sort of unusual at the time and I followed her career all that time, and it was a great honour to work with her which I’ve done several times. Back with the Rolling Thunder Revue with Bob Dylan, I toured with her for a couple of months in 1975 and through the recording of 'Treasures for the Folk Den', and she was kind enough then to give me her day off – she was on a real hectic tour, and she had one day off in Orlando and she gave it to us, so I went over there with my recording equipment and captured her singing that and also Eliza Carthy at the time. It was great fun. And working with Judy Collins, it was the same thing – I had known Judy back in the ‘60s. I was her musical director on her third album ('Judy Collins#3', 1963) for Elektra Records and Pete Seeger, I had played with him a couple of times too at that point. I’d gone to his house to record with him. Working with Pete was just an incredible thrill because I’d been a fan of his since 1948 when the Weavers were on the radio with ‘On Top of Old Smoky’ and ‘Tzena, Tzena’. And, of course, he was a big celebrity at the Old Town School. He came and played there a couple of times and it was fun. PB: Tommy Makem added a completely different colour – I’m referring to his drinking songs. RM: It’s ironic because Tommy never drank (Laughs). He was a complete teetotaller. We did ‘Finnegan’s Wake’, and at the time he explained to me that he didn’t really like the song and I understand that because of the history of the song – it was an English Music Hall song, which makes fun of the Irish. I remember him and the Clancy Brothers doing that song at the Gate of Horn when I was a teenager and so I always had a good memory of it – it’s really a funny song. I found when performing it I’d have to set up the story to explain what it’s all about because it’s got that Irish dialect in it. Hopefully people understand the verses once you do that, but when I do it in concerts people crack up. It’s a funny song. PB: What were your recollections of Odetta? RM: Odetta is another person that I saw at the Gate of Horn. When I was a teenager I used to sneak in there. I would watch Odetta and just be amazed by her and I remember talking to her on the street on the corner of Dearborn and Chicago. I remember talking to her and telling her how much I enjoyed her work. She was so sweet and so kind. She was probably in her early twenties at that point and one time I was working at a folk festival in New Jersey. I was playing ‘The Ballad of Easy Rider,’ which I’d written for the movie, and Odetta walked on stage and started singing it with me. I could hardly sing anymore because I went to tears. I was so moved that Odetta would come up and sing with me. It turned out that she’d recorded the song on one of her albums. She felt compelled to come up and sing it with me, and I thought that was so sweet. And then, of course, we recorded together on the 'Treasures' album. PB: 'Stories, Songs and Friends' includes interviews from your fifty-year career. RM: Yes, the DVD does. The CDs are concert recordings of live concerts from my mother’s 102nd birthday. She’d broken her hip so she was in bed. She couldn’t come to the concert. We recorded the concert with eight microphones and really high definition equipment so she could hear it. She did hear it, and she passed away three days after she heard it. But it was recorded for her benefit. I listened to it and I thought it was a good recording, so we released it. PB: That’s extraordinary. If you were to talk to a 14-year-old American kid about folk music, what would the reaction be? RM: They’d go, ‘Huh?’ I don’t think they would know what it is, really. Or they would think it was something that Katy Perry or Britney Spears did or something like that. Explaining traditional music is even hard for people who grew up with it because the definition of folk music is so different for different people. Some people say it’s only the ballads that happened in the 17th century, and other people think it’s the Beatles popular songs from the ‘60s. It’s got a wide range of definitions, but I keep concentrating on the songs by anonymous authors from hundreds of years ago that really should be preserved because they’re stories about real people and things that happened to them. It's the cowboys and the seafaring lads and the blues. I love the songs because I went to the Old Town School and it was instilled in me, not only the songs and how to play them, but the folklore behind them and how they came about and how Celtic music came over and was kind of distilled in the Appalachians and became what is now country music. The whole history of music is really interesting to me. PB: There was a video showing you and Richard Thompson performing together, and the fans commented on how beautiful your voices sounded together. He’s an artist also who takes guitar work quite seriously. RM: Richard’s an incredible player. There’s a saying that iron sharpens iron and one man sharpens another. That’s exactly what happened when I played with Richard Thompson. I’d go home and practice a lot because he’s so good and he really does prompt you to want to play better. I have had the pleasure of working with him several times. I think the footage you’re talking about was shot in Seville, Spain back in the 1990s or the late 1980s. it was a long time ago. We played with the Legends. Bob Dylan was there and quite a few other artists. It was a real privilege to work with him. We used to have the same booking agent, so we played together a lot more back then but I think we both have different agents now. PB: You’ve collaborated with your wife, Camilla, as well. RM: Camilla and I have written many songs together and it’s always a lot of fun. When we concentrate on it, we’ll go over to the beach and spend a couple of weeks just writing songs, and then we’ll come out with a few that we like. PB: Where are you living now? RM: Orlando, Florida. We’ve been here since 1981. I lived in California for twenty years but, because of the population density on the East coast, it was sort of difficult to work anywhere else ,so flying from LA to New York and then renting a vehicle up and down Interstate 95, doing a lot of concerts and flying back was a hassle. So, we wanted to be closer to work, but didn’t really want to deal with the cold weather. PB: What are you looking forward to when you tour in the UK this fall? RM: I’m looking forward to the travelling and being there. It’s always a lot of fun. Camilla and I love to travel. It’s kind of like an extended honeymoon and we just have a great time traveling around and playing for people. I enjoy being on stage probably as much as anything else in the world, and it’s just a great time. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/roger.mcguinn.3https://twitter.com/rogermcguinn

http://www.ibiblio.org/jimmy/mcguinn/index.html

Picture Gallery:-

favourite album |

|

Peace On You (2018) |

|

| Carl Bookstein reflects on 'Peace on You', the 1974 second solo album from Byrds founder, singer and guitarist Roger McGuinn which has just been reissued. |

reviews |

|

Born to Rock and Roll (2013) |

|

| Fabulous compilation of former Byrds' front man Roger McGuinn's 70's solo albums |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongBathers - Photoscapes 2

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Simian Life - Interview

the black watch - Interview

Chris Wade - Interview

Cathode Ray - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPTrudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Fall - Hex Enduction Hour

Peter Paul and Mary - Interview with Peter Yarrow

Sam Brown - Interview Part 2

And Also The Trees - Eventim Apollo, London, 21/12/2014.

Place to Bury Strangers - Interview

Miscellaneous - Charity Appeal

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart