Joey Molland - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 24 / 2 / 2014

intro

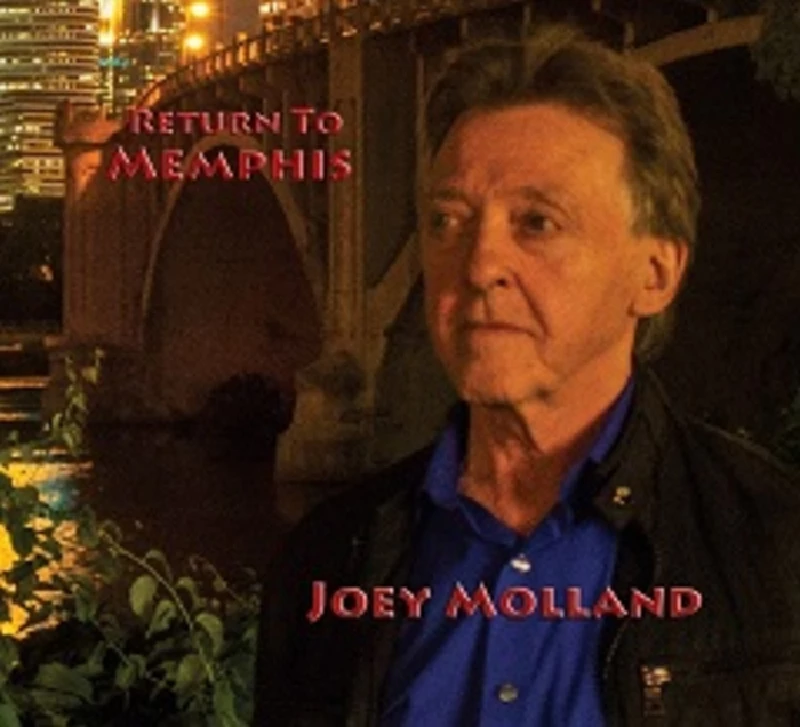

Joey Molland, the guitarist with Badfinger, talks to Lisa Torem about the bestselling 70's group, working with both John Lennon and George Harrison and his recent fourth solo album, 'Return to Memphis'

Joey Molland could be a contender for the rank of fifth Beatle. After all, he was born in Liverpool, where, much like the Fab Four, he mastered his instrument and devoured all things rock ‘n’ roll. He played with local groups: The Assassins, the Profiles and the Masterminds, devotedly putting in his “10,000 hours.” He also impressed an industry maverick, Andrew Loog Oldham, who released a Mastermind’s single on his own label, which was a Dylan cover. In 1966, Joey and two band mates, as the Fruit Eating Bears, backed the Merseys and the following year he worked with Gary Walker and The Rain. Joey contributed half a dozen songs on their album entitled ‘# 1’. After the band broke up, Joey got a gig with the Iveys, who would change their name to Badfinger, after a John Lennon demo, ‘Badfinger Boogie’. The classic line-up was: Pete Ham, Tommy Evans and Mike Gibbins and Joey, who is the one original member. Badfinger holds a special place in rock history, as they were the first band signed to the Beatles’ label, Apple Records. With their vitality and confidence, spot on harmonies, well-rounded arrangements and stellar songwriting, they soared up the charts with songs like ‘Baby Blue’ and ‘Without You’ before getting victimized by unscrupulous management, which ultimately led to personal tragedy and the suicides of both Pete Ham and Tommy Evans. Yet their contagious music has continued to reign. In interview with Pennyblackmusic, Joey enthusiastically discussed what it was like to join George Harrison on ‘All Things Must Pass’ and the Concert For Bangladesh and on Lennon’s post Beatles solo album ‘Imagine’ with Tommy Evans. After leaving Badfinger in 1974, Joey toured with Yes and Peter Frampton when in the band, Natural Gas. He also reconnected with Tommy Evans, producing two more albums. His solo albums are ‘After the Pearl’, ‘The Pilgrim’ and ‘This Way Up’ with Echo Boys. With Executive Director, Vince Gilligan, praising Badfinger’s ‘Baby Blue’ these days, and using it for the finale of the series ‘Breaking Bad’, undoubtedly Badfinger is entertaining a whole new audience. Currently Joey, with his own band, is on a Badfinger tour in the US and is promoting his fourth solo album, ‘Return to Memphis’ and, whilst Joey might convey in this interview that this recording is a departure from what his fans expect from a certified rocker, it feels, to this writer, more like an arrival, with all arrows pointing to a sign that reads, ‘Welcome Home’ because Joey’s themes are universal. Like a mixologist swizzling a tall cool drink, he washes down politics, philosophy, rock riffs and a Willie Nelson-style sensibility on one of his best recordings yet and he’s got the chops to prove it. Joey’s seen it all, done it all and knows them all,but remains one of the most humble and hard-working musicians of the rock era. PB: You did a screening at the CIMM Fest for director John Anderson’s documentary ‘From Liverpool to Memphis’. How did it go? (Chicago International Music and Movies Festival is an annual Chicago-based event, which screens music-oriented films and provides forums for industry personnel and their audiences – LT). JM: It was kind of fun. I had never done anything like that before. The reaction was really, really good. I think a lot of people who were there that day were Badfinger fans.. It did go down well. I don’t know what the general release will be like, but I think it is available – it was filmed for a charity for the San Miguel School of Chicago. Kevin Allodi sponsors it, along with a bunch of his wealthy friends. He’s a tech guy. He’s doing well in the tech world. It went well. They were happy with it and it was great to be included in the fest. PB: Was it an intimate setting? JM: It was a nice theatre with four or five screens. A small one, but a multiplex nonetheless. There was a little bar in the theatre, which I thought was great (Laughs). So everybody socialised a bit before, and afterwards I met some interesting people. John was excited to be there as was Kevin Allodi. I got to talk with some of the fans. For me, anyway, it’s weird looking at yourself on TV, let alone on a big screen like that. PB: It sounds radically different from performing for a live audience. JM: Yeah, in that format anyway. We did the VH1 show, ‘Behind the Music’, a few years ago, which was a Badfinger documentary by a guy named Gary Katz, where me and my wife talked about the band and the time at Apple. PB: Another more recent news item is that Badfinger’s ‘Baby Blue’ is getting attention from a whole new audience because of ‘Breaking Bad’. JM: It was exciting, wasn’t it? It was a complete surprise Pete Ham wrote the song, and Pete’s estate negotiated with ‘Breaking Bad’ for it. They knew about it but none of us knew about it and what a great surprise, and then, yeah, the record was number one the next day (Laughs). It was unbelievable. We’ve been really fortunate in that way. Martin Scorsese used the hit songs in some of his movies, and then ‘Breaking Bad’, of course, is the biggest TV show ever. We don’t quite know what happened. We’d had success with that record forty years ago. We got an ASCAP award for it then because it was so popular on the radio and it was a hit record, and then for this to happen. It’s actually sold more copies because of this. It’s just unbelievable. My friends are asking me, “Is that going to change your life?” It’s kind of weird. So we’re sitting here. We haven’t got any royalties coming yet, but they should start to come in about June or July, I think. It should be interesting to see what happens. Remember Mariah Carey recorded one of the Badfinger songs,‘Without You.’ It sold millions and billions of copies, and we started to get these royalty checks. It was stunning. So who knows what’s going to happen here from being a lowly musician to being on top for a couple of weeks and then right back in the battle after that. PB: Did you like the Mariah Carey version as much as the Harry Nilsson cover of that song? JM: That was great but that was all mixed up with the Badfinger stuff. We were doing very well in those days, but now we’re just moving along. I make a reasonable amount of money. My bills are paid, but when something like this happens it’s like getting a big bonus and it’s really great fun for a while and then back to just doing the work… PB: Badfinger were a great band but you had some bad luck with the management. What advice could you offer the up and coming bands, who, like Badfinger, have great material, drive, imagination and talent but are not sure how to build a team who supports them and watches their back? JM: Be careful. Try and surround yourself with friends, of course, but you can’t hire a plumber to fix the electricity. You want to get people around you who know this business and have reputations. Talk about people. Ask about people. I do that now until this day. Like when the ‘Breaking Bad’ thing happened to me, I started to call professional people in the business that I’ve met – I wasn’t necessarily great friends with them, but I’ve met them to get some counsel about it, how to make use of the fact that it happened. That’s what we all need. We can all play the guitar or play the piano and sing a song and if we’re lucky enough we can get a good tune together, but we don’t know anything about the business of music and how it works, and the characters involved. I’m still finding out about it. PB: And the business has changed so much and is always evolving. JM: It is all the time. PB: But we could probably all agree that character is character. JM: Yes. PB: Badfinger played on two George Harrison albums. During the recording of ‘All Things Must Pass’ there was so much going on. George’s mother was ill, Phil Spector had his own vision of what he hoped to accomplish and you had a room full of super stars..What was the chemistry like in the studio? JM: It was good. Everybody was devoted to George. He was a sweetheart of a man so everybody kind of got along and George invited people that he knew. Once or twice there would be a regular session guy, a suit and tie fellow. They’d come and go, some of them worked and some of them didn’t but all of the stock players – Ringo and everybody – Ringo’s a dead normal bloke, isn’t he? Eric Clapton is a very regular bloke. I don’t know about now but back then he was a regular guy. He played the hell out of a guitar – Carl Radle played bass and Klaus Voormann. These are all regular blokes. They loved playing, so it was great fun and for us to be there – it was a great thrill for us (Laughs). They put us in a blue plywood box that they made. We went inside there because we were playing acoustic so there wouldn’t be leakage. We were all thrilled about it. PB: What songs did you play on? JM: We played on most of it. We’d just go in and it would be a bit of a blur because we’d just go in at eleven in the morning and start working on songs ,and after we played on ‘My Sweet Lord’, ‘Beware of Darkness’, ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ and ‘Wah Wah’ -- just loads of song after song after song. ‘What Is Life’ – all of it, really. Even on the jams, we’d just beat along on the acoustics. It was great, great fun. When George produced us, he would bring his guitar and amp and plug in and play along too. You eventually got over the fact that he was in the Beatles; I was such a big Beatles fan, everybody was. They were years ahead of everybody. They were amazing; their songs and how good they played together. A four-piece band like that – how good they sounded when they started playing. It was a real drag when they broke up. The vocals were unbelievable and then they worked out those little bits. PB: What did you hear about Paul McCartney’s ‘Come and Get It’ session? Was he a perfectionist? JM: They told me that he wasn’t like Hitler or something,but he knew how they had to do it. And he had each of the guys sing the song. There’s a CD that has like twenty versions of it that has all of the guys singing it. He had Tommy, because he liked the sound of his voice, singing that particular song. They said he was great to work with. PB: What do you remember about performing at the Bangladesh concert, which inspired so many subsequent charitable concerts? JM: It was a really nice experience. George asked all the musicians who played on the ‘All Things Must Pass’ album if they would come to New York and do the concert, and most of them said, “Yeah.”. We went over right away with him. We flew over about a week before and started rehearsing and then everybody came in that week. We were sitting in the auditorium after the sound check. We had done a dress rehearsal the day before, and Bob Dylan came to the rehearsal and it was like the Lord showing up. Everybody was just blown away by it because nobody knew he was coming. I don’t think even George knew he was coming. We’d finished the sound check and we were waiting for the cars to take us back to the hotel. All of us were there, Leon Russell, everybody. Bob Dylan walked on stage with his guitar and harmonica and did a sound check for himself. Of course, George and Leon and Ringo ran up on stage. I can’t really remember if Ringo is onstage with him on the film. Leon is such a strong personality. But it was such a thrill and the concert went really well. George was really nervous but the show was great. Tommy Evans and I played on ‘Jealous Guy’ and ‘I Don’t Want to be a Soldier’. John called in the afternoon that day. I can’t really remember the year, but the call was that day and Tommy and I were the only ones in the house. We all used to live in a little house together in Golders Green in London. They called us and asked us to come over and play some guitars. John was recording that night and they said, “Would you do him a favour?” Of course, we said yes. They sent a car and we went over to John’s house, a big beautiful mansion in Tittenhurst Park. It was a beautiful place. We got there and the studio (Lennon’s Ascot Sound Studios - LT) was all set up. Phil Spector was there and Klaus Voormann again, and Nicky Hopkins played the piano. We’d known Nicky for years at that point; He was one of the great pianists in England, maybe the best and Jim Keltner, playing drums. And that’s all there were in the room. PB: You didn’t need anyone else at that point. JM: That’s exactly right. PB: I really enjoyed listening to your new album, ‘Return to Memphis’. You had called it barebones and I can understand that, but I would like to add that the songs were very solid and Carl “Blue” Wise, who produced it, says on his website that that is exactly what he looks for. Why did you decide to do this type of album at this time? JM: I’ve been looking to do an album for about three years, and I was really waiting for something to steer me on to doing a record. I’ve done records and I’ve got opportunities to make records. I went to Memphis to do a session for Carl, playing guitar for him and the session turned out to be at Royal Studios. When I went into Royal Studios I said, “Wow. What is this place?” because it’s a really kind of magic place. They’ve made so many records and great people have recorded there. Famous people actually worked on building the vocal booth -- Sam and Dave and people like that. I actually met Bobby “Blue” Bland while I was there. It’s a really remarkable place, and then I met the players, Lester Snell, Steve Potts and Dave Smith, and these guys were just mellow, no egos there. They were just musos and, of course, the whole atmosphere of the place got me juices going, and I remembered things about me past and I decided I wanted to make the record in the studio and that’s how it came about. I talked to Carl and said, “I’ve got a bit of a budget for a record.” I told him what that was and let’s see if we can get it together. He negotiated with the studio and got the deal together, so it was somewhat close to me budget and we settled on a time to do it and we went ahead and did it. I sent him thirty songs and he picked a dozen and he told me why he picked them. I just went ahead and jumped in his pool and swam up and down with those guys. PB: So did you have a musical formula for creating the tracks that you sent to Carl? Was there a central theme? JM: No. That’s another story. In Minneapolis where I live now, I’ve got a group of musical friends. I’ve been here about twenty five years, more than that actually, and I’ve got a group of friends here who worked in a studio. It was called Echo Boys. They told me that if I would bring a new song down once a week I could record it there for free. They’d play because they liked my songs, and I said , “Okay” (Laughs). I mean, it was a great night out. So I’d bring a six-pack and go down to the studio. I’d play one of my song ideas and we’d work on it for a couple of hours, and then record it. Sometimes we’d get one song, and sometimes we’d get two. We went on doing this, and I got into the rhythm of doing it and it got to be so that Friday or Saturday night I’d start getting ideas because the sessions were always on Tuesday. I’d start getting ideas for songs and it’s like anything else. When you get on the road doing it the songs start to come. ‘Hero’ came, ‘Walk Out in the Rain,’‘Still I Love You’ –that’s what happened and I ended up with about 30-35 songs. Carl picked out those ten, but that’s really how it came together. And I liked the demos, and we’ll put those out sometime because they’re pretty good. I haven’t been able to go back and mix the demos properly but Harry, the keyboard player, made copies and they are nice. That’s what I got my record deal with, and that’s what I sent to Carl. PB: The lyrics to ‘Trip To Mars’ were intriguing. JM: Oh, yeah. I don’t like wars. I don’t know anybody who does like wars; maybe in the movies they might be okay. Years and years ago, I think it was one of the Bush presidents, when they were running they were talking about building a ship to Mars and I had this memory and that song popped out in 2008. That’s what it is. Instead of saying, “They tell you that it’s time to go,” I should have sung “we” because I’m just as responsible for that as anybody else. It’s always been “us” and “them” in terms of the warmongers, but, really, we’re all kind of responsible for those things happening. I don’t agree with sending the guys over, and the girls now. I don’t know about intercontinental governance – trying to fix someone else’s problems for them. I don’t know about all that but that’s another world, isn’t it? But that’s what the songs are about. I think music is a great medium for that kind of thing. It gives a guy like me a time to rant a little bit. PB: ‘Frank and Me’ sounds like a more interpersonal song. JM: Frank was my eldest brother. He was seventeen, eighteen years older than me. When I was born, Frank was already out of school, working. In fact, he joined the navy. I never met this guy Frank. I’d see him when he came home. He was always nice – he’d bring me a toy gun or something. He’d bring me a lot of things. He went all over the world in the British Navy – the Royal Navy, not the merchant fleet, the one with the guns and everything. So, I never really got to meet him, and all of our lives we got on okay. We could always go for a pint, but the conversation was “How you doing?” It was a normal family conversation, but we related. He came over to visit me. He was travelling when he was retired, and he came and stayed at my house for a week, and in that week we got to sit around and actually talk about stuff we liked to do and general things and some political stuff and religion; stuff that we’d never really talked about and I had had that idea for that song, that melody for years and I could never get the lyric for it. So, it was always phonetic lyrics but I got up one morning that week and wrote the words because Frank and I had been sitting around. PB: You reconnected. JM: I think we connected for the first time. We found out we both like to do a lot of the same things. We both like to go rummage. I’m a great flea market guy -- antique stores, knick-knacks. I love all of that stuff and that’s how that song started and that’s why I called it ‘Frank and Me’. I was going to call it ‘Yesterday’ but a mate of mine in Liverpool, Bob, said to me, “That title might be a bit confusing.” PB: Was ‘Hero’ written for a particular person”? JM: No, but I have two sons. They’ve both gone off their teenage off-the-rails years, to put it bluntly and nicely. I suppose the song is inspired by - I was reading in the papers about students after university not being able to find work and then on the other side of that they go home and live with their parents, so it isn’t easy taking handouts. But you hear about the guy, the Facebook kid. He had an idea and he’s a billionaire. So, he’s the one. I tried a thing where the melody would start in the key, and then the next stanza of the melody would start a step up in the key, in the scale of it, and I was really interested to see how the melody progressed. I thought it worked really well. It’s a lovely song to sing on stage and the crowd really enjoyed it. PB: It struck me as different from the other songs. It could have come from a musical rather than from a singer-songwriter point of view. Like when you go to see a musical and the spotlight is on the singer and he reveals something the audience didn’t expect. JM: Yes, it’s a personal thing. It does communicate to the audience really well. PB: Are the same guys that play on the album touring with you? JM: No. I’ll be with my band. We’ve been together fifteen years. We do mostly Badfinger stuff in the concert. I do maybe one or two things off of ‘Return to Memphis’ because it is a Badfinger show. But I will be going out and doing more of a Joey Molland show. I’m trying to get these things set up and it’s not easy. That’s for sure. PB: You really want to play but you end up doing everything else. That’s what I hear from so many musicians. JM: You’ve got to deal with everything. Everybody does it out of their house now. I’m trying to set up a little theatre tour for September and October. I am doing some solo acoustic shows. They’ll probably be out in the West Coast. I was just up in Syracuse. I’ve done a few up there. I’m going to the University of Fredonia in April. I’ve been up there and I’ve kind of done a storyteller-archive show there. They have a great music programme, and they’re really ambitious. They’re looking to create a good archive and having people go in and talk to students, play some songs, talk about writing and the career aspect of it. It’s interesting. It fills your time up. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

John McKay - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Prolapse - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeDavey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Blueboy - 2

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart