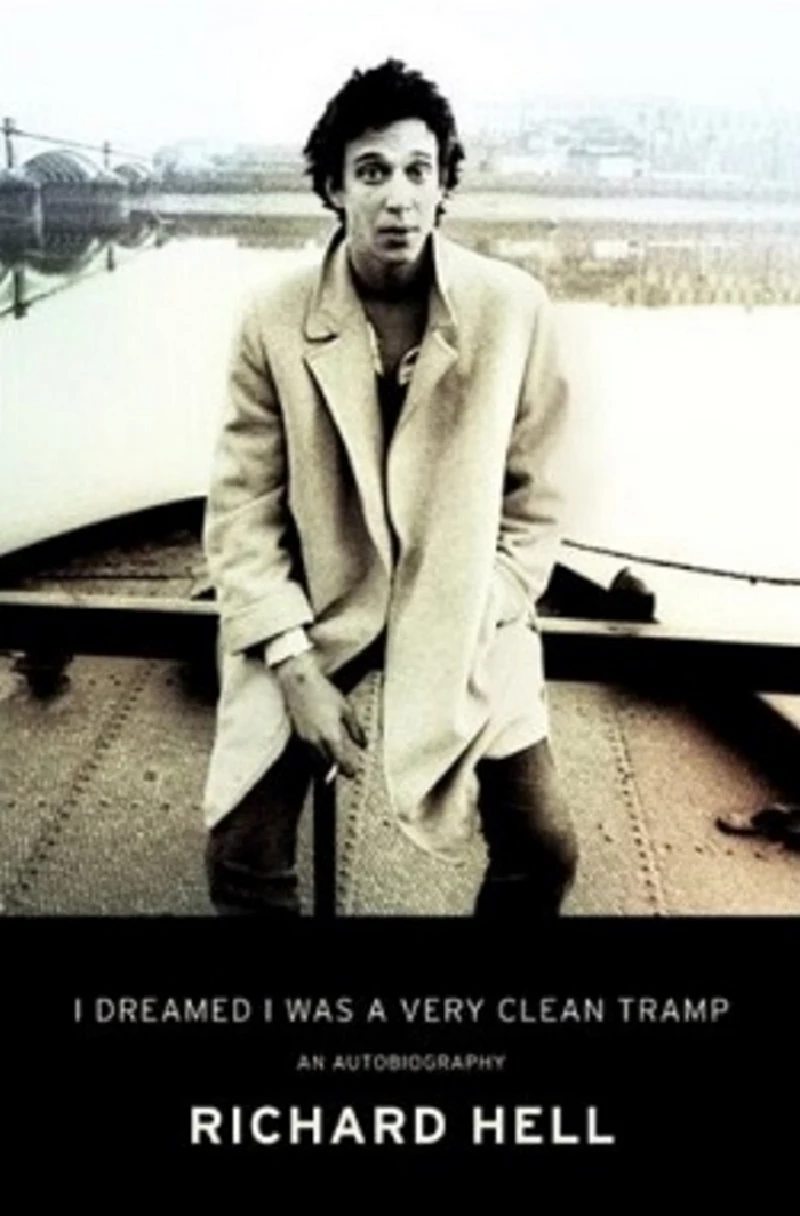

Richard Hell And The Voidoids - I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp

by Adrian Janes

published: 31 / 8 / 2013

intro

Adrian Janes examines 70's punk icon and Voidoids front man Richard Hell's new autobiography, 'I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp'

Richard Hell was one of the key figures of the New York music scene of the 1970s, as much for his ideas as to what rock and roll could and should be in terms of image as any actual musical contribution. The book ends at the point where he abandoned his fitful career in the early 80s, due to a combination of disillusionment and the overwhelming need to end his drug addiction. Apart from a brief foray on disc in the 90s with Dim Stars (a group which also featured Thurston Moore and Steve Shelley of Sonic Youth, and which showed that he could still turn out a twisted tune on occasion), he has since worked as a professional writer with journalism, novels and poetry all to his name. This book contains a number of surprises, certainly if you approach it expecting only the recollections of his years as a cult rock figure. Hell starts with his Kentucky childhood and increasingly rebellious teenage years. One important incident from the latter period is when, having been suspended for drug-taking at school, he and schoolfriend Tom Miller (the future Tom Verlaine) decide to drop out and head to Florida. Their hapless efforts to keep warm by starting a fire in a field lead to a conflagration and arrest. Subsequently Hell is able to persuade his mother to let him leave school altogether and go to New York (while still only in his late teens) with vague aspirations to literary success. The preoccupation with writing at this stage is something of a revelation. Although the literate nature of his lyrics is one of the key attractions of the Voidoids’ songs, I had thought that he had plunged fully into writing only later, as a result of his failure to make it in music. But in the late 60s music seems only incidental to his life, even if certain records and bands such as the Rolling Stones are recalled as having had some impact on him. What dominates is poetry, although his efforts seem to have been confined to the world of little magazines and cheap pamphlets, with no real attempt to become part of any literary circles or meet other writers. The main exception to this is Verlaine, with whom Hell reunites in New York. Having jointly created a book by fictional poet Theresa Stern, they eventually light upon the idea of pursuing music. This evolution seems somewhat mysterious (especially as at this stage Hell couldn’t actually play the bass he eventually took up), although the emergence of Patti Smith and her gradual inclusion of musical elements to complement her poetry readings evidently influenced them. Hell describes Verlaine in this period as “imagining his future as a professional singer-songwriter” but doing little to achieve that goal. Becoming a band seems to have been almost a premeditated art project on Hell’s part rather than any desire to be a musician, since it would allow him to write but also to express himself through ”singing, clothes, haircuts, names, posters, interviews, etc”. A sense of excitement begins to grow in the book at this stage, firstly the false start of the Neon Boys, and then Television begin to take shape. Hell describes early rehearsals with wonder, like some kind of musical anthropologist discovering his own tribe: ”The sounds that came from the amplifiers were absurdly moving and strange, the variety of them so wide in view of the fact that they came from flicks of our fingers and from our vocal noises... a single thing, an entity, that was produced by the simultaneous reactive interplay of the four band members.” The excitement is also found in the development of the wider New York scene, as bands like the Ramones, the Stilettos (the precursor of Blondie) and Talking Heads begin to emerge and follow Television in playing the club at its centre, CBGB’s. In Hell’s account, once Television are playing in public Verlaine becomes increasingly dictatorial and gradually freezes him out of the band. The high value Verlaine evidently placed on musicianship compared to Hell’s looser, more spontaneous attitude raises the question of how they managed to collaborate as long as they did. Listening to the albums ‘Marquee Moon’ and ‘Blank Generation’ one after another, great as they both are, clearly reveals two very different sensibilities at work. Around the same time he leaves Television, the New York Dolls also finally collapse while managed by Malcolm McLaren (their acquaintance making him aware of the spiky haircut and torn and safety-pinned clothing Hell had pioneered). Hell is invited to join the Heartbreakers, the new band Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan are forming in the wake of the Dolls’ split. He had already been an occasional user of heroin, so joining a band with two confirmed junkies was probably not the way to go to avoid deeper involvement. In any case, he comes to realise that he wants to create more ambitious songs than Thunders and Nolan do. This level of ambition, and meeting the misfit guitarist Bob Quine, for now trumps what is gradually turning into a full-blown addiction as he decides to form his own band, the Voidoids (a name also used for his first novel). He is rightly generous in his praise for Quine’s musicianship: “He assumed as fundamental the qualities that were the highest aspiration of most soloists, and he would then depart from that platform into previously unknown areas of emotion.” Quine himself was several years older than anyone else on the CBGB’s scene, balding and conventionally dressed. Though admittedly Hell insisted he change his physical appearance to fit better with the band’s look, credit is still due to him for recognising and fostering the talent that no-one else had. Yet despite putting together an accomplished group and making the landmark 1977 album ‘Blank Generation’, Hell’s mounting heroin dependency and consequent self-absorption fatally undermines the Voidoids’ ascent, though they’re not helped by incompetence from both management and record company - for example, the album isn’t released in Britain in time for their tour supporting the Clash. His observations on the Britain that punk erupted into are fascinatingly pitiless: “The streets of the East Village were burnt out and lawless, but they were Joyland compared to the death row oppressiveness of urban Britain,” but this outsider’s perspective also gives him insight into why the Sex Pistols and punk music generally could take off here whereas the New York scene of which the Voidoids were part only really represented itself. He’s also perceptive about some members of the then British music press and their efforts to be punk cultural commissars, such as Julie Burchill, “a self-adoring, super-ambitious loudmouth” - something that it took many British readers years to realise. During this tour, and no doubt partly because of his junkie sickness (harrowingly described), he decides he wants to quit music. The impression of the whole thing having been less about music per se than a sort of artistic experiment returns: “Once I’d made the album, I’d accomplished what I’d set out to do...to have an impact on the world, to make myself heard.” Apart from some acting roles in films and occasional gigging, his life over the next few years seems to be largely given over to his heroin addiction, which doesn’t stop him indulging in other drugs as well. A second, final album ‘Destiny Street’ is made in 1981 (Quine the only other member remaining from the ‘Blank Generation’ days), critically acclaimed but having little impact beyond that Hell reaches a decisive crisis when to feed his habit he firstly steals the drug stash of his friend Cookie Mueller and then, living in Paris in a bid to write a book and get free of drugs, is unfaithful to singer Lizzy Mercier, the most passionate and profound of all the many romantic and sexual affairs scattered through the book. Hell writes vividly, and his pen portraits of others such as Verlaine, Quine, Patti Smith, Peter Laughner and Lester Bangs are honest evaluations, generous to their talent and intelligence but not flinching from their faults. It should be added that, justly convinced as he is of his artistic abilities, he is unsparing when it comes to his own flaws, especially those which wrecked relationships and stalled his musical career. Anyone with an interest in that artistically fertile place and time that was New York in the mid-70s should enjoy this book.

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

John McKay - Interview

Loft - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart