Thomas Newman - Interview

by Mark Rowland

published: 29 / 10 / 2012

intro

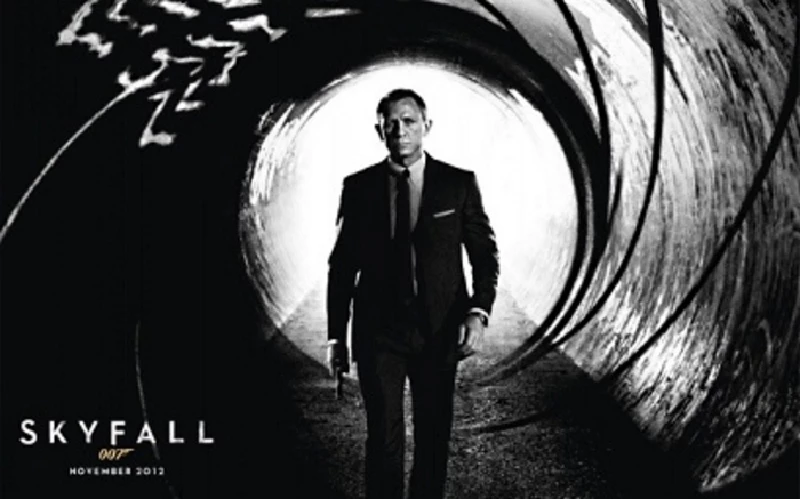

Mark Rowland chats to American film composer Thomas Newman about his soundtrack for the new James Bond film, 'Skyfall'

There are a lot of unsung heroes in the film business. The stars, directors and producers tend to get most of the limelight, but a single film employs hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people, many of which will remain unknown outside of industry circles. There is a sort of second tier of people in the movie business, however, many of which are fairly anonymous, but are often recognised and respected names among film buffs. Some of this second tier will also rise into the wider public consciousness. This second tier includes screenwriters, cinematographers and, most importantly in relation to this article, composers. The score to a film often affects you without you realising it. Your emotional experience in the cinema is often indelibly linked to the score of the film. Listen to the score away from the film that you’ve seen, and it can recreate that emotional experience away from the story it was connected to. Some scores also capture the public’s imagination in a wider way, often, but not always, because the film itself has captured it in the first place. Those famous film scores that top most people’s best score lists are the ones linked to a personal nostalgia; a memory of childhood, a slice of life from a specific year, the exhilaration of a life-changingly good film. That is how many scores are discussed for the most part, which both highlights what’s great about a film score while also drastically underselling them. The people that write film scores put together a complete piece of instrumental music – often richly textured orchestral stuff – in a matter of weeks. They are jobbing writers, without the luxury of time to build up material for their next album. The fact that that work can be as emotionally rewarding as any great classical work and as experimental as any of the best avant-garde compositions is testament to their skill. Thomas Newman comes from a family of film composers, including his cousin Randy Newman, brother David Newman, his uncles Lionel and Emil Newman and his father, the legendary composer Alfred Newman, one of the three godfathers of film music (alongside Max Steiner and Dimitri Tiomkin), winner of nine Academy Awards and the third most Oscar-nominated person in history. Thomas Newman hasn’t done bad for himself either. He has been Oscar nominated ten times, and has won BAFTAs, Grammys and even a Classical Brit Award for his work. Throughout his career, he has scored a number of highly-regarded modern classics, such as ‘The Shawshank Redemption’, ‘American Beauty’, ‘Road to Perdition’ and, most recently, the latest James Bond film, ‘Skyfall’. Newman has worked with the director of ‘Skyfall’, Sam Mendes, on all but one of his films, commencing with Mendes’ debut film, the aforementioned ‘American Beauty’. But this score was a much different proposition than their previous collaborations, bringing with it a number of expectations and conventions inherited from its 23-film legacy, and a theme that is so well-known and well loved that the pressure was on both the film and score to really deliver, particularly after the disappointing reception of the previous Bond film ‘Quantum of Solace’, which many people felt veered to far from what made Bond great in the first place. Thankfully, both Mendes and Newman have pulled off their respective tasks. The score to Skyfall, like the film itself, is a modern twist on classic Bond; fast paced and diverse, with variations on John Barry’s original theme threaded throughout, sometimes subtly, sometimes brought to the fore, but never quite the original theme itself. But beyond the excitement and glamour of the score, there is real emotion and moments of beauty, something that Newman excels at. Newman’s musical voice can often be playful, sometimes busy, sometimes ambient, but it never strays too far from the emotional heart of the story. It’s what makes so many of them so memorable. PB: How was the ‘Skyfall’ premiere in London? TN: It was amazing. Pretty spectacular. A real spectacle, so many people. It was great. PB: When scoring a Bond film, you almost have to work within two sets of conventions; that of the action genre and the expectations and conventions of the Bond series. What was it like working within those conventions? TN: It was daunting and tough, because you’re right. The theme is so beloved and rightly so. It’s a great theme and it says so much about the character, and it’s one of those tunes that if you hear it, you almost want to applaud, so you have to kind of acknowledge it, but also acknowledge the sense of action and danger. I think the great thing about Bond is that it can be all these things at once; fun and danger combined, and swagger and sexiness and all that kind of thing. So it really rises above my personality to the personality of the film and the character and franchise, and that was hugely challenging for me. PB: Pieces of that theme appear throughout your score, sometimes in rather subtle ways. Was it fun to play about with that theme and twist it into new shapes? TN: It was. Sometimes if you’re lacking an idea, or there’s a bit of a gap in your tank, it’s just a way to carry on with that tradition. So yeah, there were moments of real kind of creative refreshment for me to say “We can quote the Bond thumb line here, of the more, you know ‘dee dah dee dah’” – you can do it at these moments that really made it stand out so that was a lot of fun. PB: Another thing about the Bond films is that they’re usually fairly globe-trotting stories. What opportunities does that give you to play with different styles? TN: I guess the thing about action is that it really wants to operate in the present tense. Wherever you are, location is part of present tense and obviously action is as well, so to have all that stuff kind of there opened up a lot of useful possibilities, which you really did want to exploit. PB: You’ve worked with Sam Mendes on all but one of his films. Is working with each other second nature, now? TN: It is and it isn’t. Relationships with people you’ve already worked with is always a comfort on the one hand, but it is not as if it’s any easier on you because of that. Even though the trust level is high, so is the expectation level, and I think the expectation level for Sam was particularly high, even in his own milieu as an action director. So I think he liked having me on, but I don’t think he was going to cut me any slack ¬– I don’t think that Sam’s that kind of guy anyway. He has a remarkably sophisticated ear, so you really can’t get anything by him, he can hear everything down from notes to performance, He is very, very hands on. PB: So he gets quite involved when it comes to the music? Does he have very strong ideas for the score from the start? TN: It’s good because mostly with him, his notes are not random, and his ideas are strong. Sometimes you can work with a director who’ll say something on Monday and something entirely different on Wednesday. With Sam, he’s consistent with his remarks, so you do feel like when you’re making progress, you really are making progress. It’s great working with Sam,. He is a very, very bright guy and he’s got great instincts. Plus I think he’s got a real sense of how to finish a movie. When it comes to post-production, I think he really enjoys how to manipulate film editorially and how sound and music can help story. So it’s fun on that level to work with him, because I think music matters to him. PB: Do you feel comfortable offering your own suggestions if you feel something doesn’t work? TN: He depends on that. I don’t think he wants anyone just to lie flat and say, “Yes, Sam. Of course, Sam.” At the same time, you want to offer up suggestions to a point. There’s nothing worse than trying to push an idea on anyone that doesn’t like the idea. I mean, there’s moments you can push, and then you have to know when to stop pushing and the idea you like is never going to be liked as much as you like it by the director. So it’s how you relate to a director and how you move forward. PB: I think it’s fair to say that you’re not particularly well known for your action scores. What was it like to work on something so action-packed? TN: It’s not easy, in so far as there’s way more notes and there’s way more requirement for music to change as action changes just so that it can exist in the present tense; what’s exciting now and what’s exciting ten seconds from now and 30 minutes from now. I’ve had experience writing action, but typically not entirely through a movie, so I’m not inexperienced at it, but it’s not really where I live or where I’ve lived in the past as a composer. I think I needed to prove to everyone that I could take it on. PB: I’d like to ask you about the general composition process: at what stage do you get involved in a film? TN: In any stage. It could be a movie that’s a year out from being made; it could be in production, or just in post-production. I could start by reading a script, or in some cases, I see a movie and I’ve not read the script. Sometimes that’s one of the best things that can happen because when you read a script, you end up having expectations that are often defied by the movie that you see, and you have to discard those expectations. It can happen any number of ways, and I don’t know which is the best way. Some people think: “I want to start on a movie really early and really be able to talk and collaborate with the director,” but in many instances, I’ve found that that’s really not the case. More time does not necessarily make for a better product. PB: What is it that you look for in a project before you decide to take it on? TN: I guess the emotional and dramatic content, really, and how I can relate to it musically. Is it something that would interest me and compel me, or is there something from the script or from the movie that I’ve seen that makes me think that I could do something original and have some fun? And oftentimes you never know, by the way. You take your best shot and you hope it’s the right choice you’ve made. Sometimes the best decisions you think you’ve made end up being the worst and vice versa. PB: Once you’ve come on board with a project, where do you start? TN: I try to be as free and as easy as I can to begin with, with the idea that it’s never going to be more fun than just throwing any idea at an image to see what it does to the image. I try not to come in, typically, with a pre-conceived idea though. I may sit down and improvise. I may take out an old idea that somehow I think relates and put it up against the image and as passively as I can, as an audience, ask myself if the idea works or if it doesn’t and if so, why or why not? Therefore I’m not associating any of my sense of myself or my idea with how it hits me when I watch and listen to it. And when I start to discover ideas that work, I ask myself why. That starts to inform what I want to do and I start to refine that, then I start to fill in the blanks, for example: if this works here, would the same idea work there? Does it want melody? Is it more percussively or ambiently based? I try to take practical measures as opposed to overtly poetical measures. PB: The process of scoring a film is very collaborative. What are the benefits and challenges of working in that way? TN: Well the benefit is, you kind of know where you stand, and you’re not talking or arguing with a director about why an idea does or does not work – I mean you can, but it usually results in the director saying: “Well, I don’t care what you think, because I don’t feel the same way.” To a degree, it becomes very clear, and that’s always good in a situation where the director’s smart and you like the film. There are some moments where you don’t agree with the interpretation, with how music is affecting drama and what the drama is doing. Something I like might be something a director doesn’t like as much because he sees it and can define it in a way that I don’t agree with. But I love collaboration; I think we’re all better in life when we’re team players. I approach collaboration with a director in the same way I do with players – I like to bring players in and I like them to participate creatively. I’m not interested really in having power over people, so my sense of autocracy is as inclusive as I can make it. I really want contributions from my musicians, because I think ultimately people are most interested when they’re asked to do creative tasks, and I want to get my players to that place where they’re contributing creatively. And I think by the same token, when I talk to a director, I want to learn those same things. I realise that it’s not my movie, and therefore my ideas have to be in service to someone else’s ideas and vision, but I want to challenge those ideas and visions as much as I can until I’m told: “No”. Then I feel like I’m doing my very best to write music for someone else’s film. PB: You’ve written some very memorable scores in the past, ‘American Beauty’ being a standout. Do you ever get the feeling when writing if a score is going to be particularly remembered? TN: It’s a dangerous thing to think. You can sometimes, but oftentimes, movies like ‘American Beauty,’ they’re a little bit of a perfect storm. The movie really helps the music and maybe the music helps the movie, but together, they turn into something that people really enjoy. There are many scores that I’ve written that are all but forgotten that I think are really good. I think, in many cases, the music kind of goes the way of the movie and maybe doesn’t have that long a life or doesn’t see as much light of day as other scores. I think the minute you start saying: ‘ Ah this is the one,” you get in trouble. You kind of want to work day to day and make the best creative choices you can make, and ultimately enjoy the music you make. I think, in the end, that’s the biggest value I can give to any director, having fun and enjoying the process of making music, because I think that really shows. PB: What would you say was your most underrated film score? TN: Oh, wow. Uh, I did a movie called ‘Flesh and Bone’ back in 1991 that I thought was a breakthrough score for me in how I combined ambient sounds, found sounds and sampled sounds with a string orchestra. It was a real breakthrough for me conceptually, so it’s a score I like that I bet not a lot of people have heard. But uh, oh gosh, I don’t know. They’re all my children, you know. PB: A lot of people in your family are film composers It almost seems that your path was paved for you. Did you have a sense that you always wanted to be a film composer? TN: Oh no, I never thought I’d do music. I studied music as a kid, but I never felt – you know, a funny thing about studying music is that oftentimes, when you learn a piano piece, and you’re always in a state of learning it as opposed to a place where you’re just making music; you never get to the fun part of making music. I think my education was that way; I was so busy trying to do something right that I never really knew what music was and I kind of went into writing because I didn’t feel I could play well enough or conduct well enough and I though, “Well, maybe, I can find some personality in myself through writing. “ It came little by little for me. I think a big breakthrough for me was this idea in my mid-twenties that no one was really paying any attention, so who was I trying to please? So I started, at the age of 26, 27, just trying to please my own ears. I think I was kind of born then in my own mind as to what I liked and why, and how I could refine my voice, my sense of music. It was never obvious though, it was not foregone that I would do this. I thought, to begin with, it was one thing to write a piece of music, but to write 50 minutes of music in three weeks; who could do a thing like that? It was a terrifying thing to even imagine. Part of me feels that having a career in this is kind of accidental, as much as you might argue that it’s obvious because I’m from a family of musicians. Maybe it was, but it was never obvious to me. I never thought I’d do movie music for a living. PB: Your father was a pretty inspirational composer. Once you decided to try your hand at writing film scores yourself, were you able to extrapolate any lessons you may have learned from your father while you were growing up? TN: Oh yeah. I don’t think I’d be talking to you here today if it weren’t for my dad. I mean my dad was the oldest of ten children who grew up in poverty, and my education, everything about my life, I kind of attribute to his hard effort and work. In the very early days – he died when I was pretty young – we’d go down and watch him conduct, and as a 10-year-old boy, you get bored pretty quickly, ironically. I’d see how he’d conduct an orchestra, and I’d see the lights dim – in those days, and I guess sometimes it’s still done today, they’d use desk lamps and because they were projecting an image, the stage would go dark and a black and white work print would come up and he would start conducting, and those are indelible kind of screen memories for me of my father. So you’re absolutely right; in retrospect, I feel very blessed and lucky to have had this window into his life and his work. He began right at the beginning, I think, in 1930, he came out to Hollywood from New York City and started working with Samuel Goldwyn and Irving Berlin. PB: What are you working on next? TN: I’m just about to start work on a movie with Stephen Soderbergh called ‘Side Effects’ with Jude Law. I’m just beginning on it, so there’s not much I can say about what I’m doing yet. But in a couple of weeks, I will. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongBathers - Photoscapes 1

Armory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Bathers - Photoscapes 2

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPOasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart