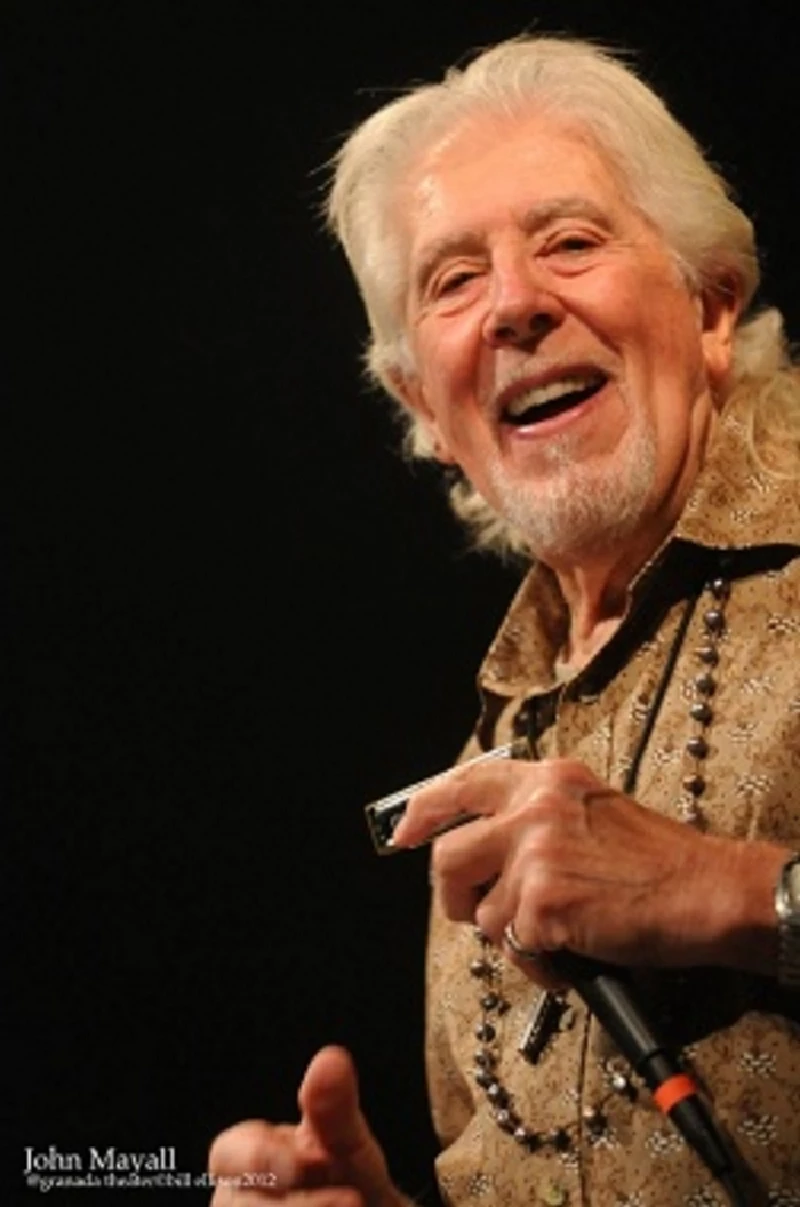

John Mayall's Bluesbreakers - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 27 / 8 / 2012

intro

Lisa Torem chats to influential blues musician John Mayall about his lengthy career and legendary band the Bluesbreakers, and working with musicians such as Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor and Frank Zappa

In the winter of 1928 Pinetop Smith recorded ‘Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie’, and it would be the first time this catchy phrase would appear on a record. The name reflected a lively, rhythmic, eight-to-the-bar style designed to be heard above the noisy American barrelhouses where it was primarily performed, and this style of piano playing was so remarkable that legends like British-born John Mayall would not only gravitate to it, but incorporate it into his unique, overall blues-sound. Mayall, not only a pianist, but a harmonica and guitar player has had a stunning career. As a bandleader, he cultivated a fan base by merging talents with Eric Clapton, Peter Green, John McVie, Mick Fleetwood and Mick Taylor. Of course, these musicians would go on to become members of Fleetwood Mac and the Rolling Stones, but Mayall would also continue to grow and advance his vision, experimenting with unorthodox musical textures ahead of his time. Surprisingly, though, in the late 1960s, he would go acoustic with ‘The Turning Point’, on which the infectious, blues-harp masterstroke ‘Room to Move’ would obtain gold status. He would also move from England to LA’s Laurel Canyon and explore jazz and rock, and enjoy the company of American rockers like Frank Zappa, while remaining inspired by his British counterparts. By the mid 1980s, he had joined forces with guitarist Coco Montoya in another incarnation of his legendary Bluesbreakers. He would also receive a Grammy-nod for ‘Wake Up Call’, a project that included the talents of Buddy Guy, Albert Collins and Mavis Staples. In the next decade his band would feature guitarist Buddy Whittington and their collaboration would last ten years. Though Mayall would need a hiatus from the feverish pace of his musical existence, he came back to the scene after being offered a project with Eagle Records. On his 70th birthday, he renewed relationships with friends like Eric Clapton for a UNICEF benefit, performing in Liverpool. In addition, his life has been documented in the BBC’s ‘The Godfather of British Blues’, and he has been awarded an OBE for devoting a lifetime to the blues. On the wings of a grand tour, and with a new studio album ‘Tough’, his debut with his quartet, released, John Mayall spoke frankly to Lisa Torem about what it has meant to be a musician both then and now, and on the talented musicians with whom he has shared the stage. PB: You have worked with a string of great guitarists and I’m wondering what you’ve learned from each other: Buddy Whittington, Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor… JM: Well, they all have their individual styles. They’ve all meshed in really well with everything I’ve done. PB: Were you surprised at the directions that any of your colleagues took? JM: Not really. I believe in these musicians, and there’s really no surprise that other people can recognize their talent. PB: Has it been challenging being an actual bandleader? JM: Not for me. It’s always been the easiest part of everything. I can’t imagine myself being a musician for hire – it’s never really been a thing. I think a bluesman has a role in expressing his emotions and talents through his music and the stories that he tells so that’s really about the size of it. PB: I wanted to discuss a specific song from the album ‘The Blues Alone’. ‘Marsha’s Mood’ was a particularly beautiful song. What inspired the chord progression as well as the spirit of that tune? JM: Well, it’s very hard to explain how a song comes to be. There has to be an emotional connection behind the story and you just put it into words and music. I don’t know. I just sit down and play (Laughs) with a story in mind or a person in mind and it just comes out. I can’t explain it better than that. PB: You’re a multi-instrumentalist, but which instrument has been your best writing tool? JM: Well, the keyboard; obviously that’s the main instrument in my life. I play a bit of guitar here and there and harmonica is a lead instrument, so that really doesn’t lend itself to be a compositional item. It really comes from the keyboard. PB: Some of your influences have been Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson and Pinetop Smith. But how did you arrive at your sound? Did you listen to recordings? JM: It was before albums were invented. I was listening to 78s. My initial collection was mostly centered on boogie-woogie music. That really was my starting point for the keyboard. PB: Do you feel that boogie-woogie will remain part of our musical culture? Will it continue to be passed on? JM: Absolutely. It’s been going on for many, many decades and it’s here to stay. I think there are certain lulls in the popularity of blues but it always comes back. It only takes one person to reach a high profile thing, like an Eric Clapton or a Bonnie Raitt or a Stevie Ray Vaughan, to draw people’s attention back to the music. PB; You’ve added texture to your compositions by using some unorthodox instruments like the sackbut, an actual steam locomotive and a celesta. What prompted you to use instruments that are not normally associated with the blues? JM: Well, they’re all part of the story. I’ve done a couple of songs that had to do with trains, so if it was a thing inspired by trains it really helped to throw in a little extra colour there that wasn’t a musical instrument. It all adds to the atmosphere. PB: When a label remasters an album, does that make a big difference to you? JM: I don’t really know what effect it has on the public but if they remaster it I guess they’re not doing anything to alter the music as far as I know. PB: In the 1960s you moved to California, lived in Frank Zappa’s house and developed a new style. It seemed like your music became more inspired by a personal philosophy. What do you recall about those days? JM: It was very exciting, obviously, when you first start playing American music. I certainly never expected at that time in the early 1960s to be going to America, but thanks to the Rolling Stones and Cream,that’s how all of the British music started to infiltrate into America. I just followed the crowd. Cream, with Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce, that connection with me, I think that really helped to get me started over here. PB: And when drummer, Jon Hiseman, and saxophonist, Dick Heckstall-Smith, left the Graham Bond Organisation to join the Bluesbreakers, how did that impact your musical vision? JM: There was a lot more jazzier influence, I think. Jon Hiseman is a jazz drummer, basically. That really kicked us into a different sort of field, and, of course, Dick Heckstall-Smith being a jazz tenor player, that was an element that steered us into the jazz-blues fusion days. PB: At certain times in your career you had a bare bones set up and yet you came up with some sophisticated material, like ‘Room To Move,’ for example. Do you have a preference for a big sound or is isolating an instrument the way to go? JM: That’s hard to analyze. I think the main thrust of any band that I put together is to reflect what I’m feeling musically, so there’s been big bands and there’s been smaller ones, and the one that I’ve savoured most consistently has been the quartet format. PB: So when violinist Sugarcane Harris came along, were you nervous about exploring another new sound? JM: Oh, no. Sugarcane was a great player and he was just very glad to have a gig with me, so it really was a wonderful experience. PB: You collaborated with John Lee Hooker on ‘Padlock on the Blues.’ How was that? JM: It was a little difficult because John Lee doesn’t stick to any set chord sequence. It was a little awkward but we’ve been friends since the early 60s. We got along great in the studio, and I just put together the best I could with what we came up with. PB: From about 1967 to 1973, you were extremely prolific, recording an album a year. Was it difficult to keep coming up with recording material? JM: No, not really. If I had the opportunity it would be the same today, but the industry has changed so much that nobody asks to get a new album every three or four months. That was the days in the 60s when we had that opportunity with record companies, but not anymore. PB: You have worked with guitarists like Buddy Whittington and Coco Montoya for long stretches of time. How have you kept each other motivated? JM: It’s particularly down to the musicians and the personalities and how much you enjoy playing together. It’s really as simple as that. As long as everybody is having a great time and able to express themselves through the music then you have it. PB: On your 70th birthday concert, was it fun getting together with old friends? JM: Yeah, it was really exciting. I hadn’t played with Eric for a long, long time, many years. He just came to say “hello” the day before the concert, and basically we didn’t do any rehearsals because we just got up onstage and did it. Basically it was very spontaneous and very exciting. They captured us on video and on audio. PB: When you say that you just get up onstage and play without rehearsals, is that because you are all grounded in traditional tunes? JM: Yes, exactly that. The blues is a language that we totally understand and it just feels totally natural. PB: What would be important for you to share with musicians who are only now exploring the genre? JM: I would think to absorb the past, but also to look for your own original way of expressing yourself. That’s what it is. It is a personal thing so if you can get something that sounds like nobody else, and that is grounded in the medium, that’s all I can suggest. PB: When you say “something that sounds like nobody else,” how has that worked for you? A particular riff, a particular feel? JM: No, not really. You don’t analyze it, if you have a musical personality…it’s just there so – it’s not something you decide or plan on. It’s just how you feel and how you express yourself. PB: When did you discover that you had a musical personality? JM: I don’t really know. You’re just born with it, I suppose. Just like writers, you naturally go into something that you feel comfortable with. PB: Were there musicians in the family? JM: My father was a part-time guitar player so he did dance music and jazz-orientated music. That was a good start for me to hear that kind of music. PB: You are about to go on a very ambitious tour through the US and Europe with a line-up of musicians, with whom you’ve recorded your first album together. According to what I’ve read, when you saw guitarist Rocky Athas play live, you knew he was the guy. What attracted you to the sound of the current line-up? JM: It’s exactly that. People that have a way of playing, that you’d love to play with them. That’s the advantage of being a bandleader. You don’t have to do anything except give them a call and see if they’re interested in joining the band. That’s the way it’s always been. PB: Rocky is from Texas and brings that sound, while Greg Rzab and Jay Davenport draw from the Chicago blues, and each of these musicians have had a wide range of influences from their own ghosts of the past. How do you blend these styles? JM: You don’t think about it. If I choose a musician, I love the way he plays and what he has to offer. It’s something that I never really have to think It’s just like a no--brainer. PB: Do you have heroes in common? JM: Yeah, I think so. I don’t know who they’d be, but overall that’s probably a big part of it. PB: Who would be your blues harp idol? JM: Sonny Boy Williamson is probably my favourite out of all the harp players, but there have been so many great ones. His style was what I started off following or trying to follow. PB: And you even wrote a piece for him… JM: Yes, I’ve done a song about him, ‘Sonny Boy Blow’ on the ‘The Blues Alone’ album. PB: How do contemporary players measure up in contrast to traditionalists like Sonny? JM: There’s a great many harp players who just wail away with a million notes a minute and I’ve never been able to get involved listening to that. PB: Now your current band recorded ‘Tough’ in a relatively short amount of time. With this being your 57th album, is this generally how things happen for you in the studio? JM: If you’re with the right musicians, we all speak the same language and it all falls into place naturally and then you know you’ve got the right people. PB: On the album there is a great deal of diversity and a few originals. Can you comment on some of the tunes and why they’re important to you? JM: If I make an album, I want to make sure there’s a lot of different light and shade in it and different subject matter so I’m very pleased with the way it all came together so quickly and naturally. So, like I said, if I’m putting together an album I want to make sure that each track sounds very different from each other so it sounds like a collection of singles. PB: For someone not familiar with the genre, which one would you suggest they hear? JM: God, I can’t even remember what they were. (Laughs) PB: Well, ‘Train to My Heart’ has that driving beat, while ‘Slow Train to Nowhere’ is more of what I would consider a dreamy shuffle, and ‘An Eye for an Eye’ is very upbeat, but philosophical. JM: You’ve really got me there. There’s a couple there that we include in our set, ‘Nothing to Do with Love’ is one of the ones that we enjoy playing live, but a lot of them are suitable for recording only, studio songs only. They don’t translate very well into live performance. PB: On this upcoming tour, you’ll be playing at local venues as well as festivals. What’s your preference? JM: They’re all the same as regards communication. It’s very nice to have a large festival audience or a small club. They both have their qualities that are very distinct and they bring out a different kind of a feel, I suppose. But I enjoy them all and I think, on a weekly basis, when you play every night, it’s nice to have that variety. PB: What are you most excited about on this tour? JM: The European tour or the US? PB: Actually, both. Was the decision made early on that you would do both? JM: Yeah, we do over a hundred shows every year so it’s always divided up into as many places that they want us to play for. The whole idea when we go out on the road is not to have any days off, if at all possible - that’s usually the way we work, so we’re working every night, not spinning wheels and wasting time in hotel rooms. PB: So you don’t get out at all and you don’t get tired of just work, work, work? JM: Well, work is pleasure. We don’t do any sightseeing really. We never have any time for that, but we really enjoy playing together and that’s what it’s all about. PB: Last question. You can invite any musicians, living or not, to play with you.Who would they be? JM: Well, it would be very nice to play with Freddie King or Sonny Boy Williamson, again. I really got on well with both those guys and they’re both way up there in… the Gods. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 592 Posted By: Myshkin, London on 26 Sep 2012 |

|

Lovely interview, Lisa, giving a great insight into the man.

|

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Blueboy - 2

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart