When Julien Temple’s documentary about Dr Feelgood, ‘Oil City Confidential’, went on national UK cinema release in May, having been premiered at the London Film Festival the October before, it brought overdue recognition to a band which had regularly been under-acknowledged and more often had been totally forgotten in musical folklore. Dr Feelgood’s influences were mainly in blues and rock and roll, but, in singer Lee Brilleaux’s rasping vocals and menacing mannerisms and guitarist Wilko Johnson’s trademark jerky guitar work, they were an early inspiration on the punk movement. Joe Strummer formed the 101ers, his band prior to the Clash after seeing them, and the young John Lydon also attended their gigs. Dr Feelgood were formed in 1971 on Canvey Island, a faded holiday resort, on the Essex coastline, and which surrounded by huge oil refineries is known by locals as ‘Oil City’, thus giving Temple his film’s title. As well as Brilleaux and Johnson, Dr Feelgood also consisted of two other local musicians, John “Sparko” Sparks on bass and John “The Big Figure” Martin. The group became embroiled in the mid 1970’s “pub rock scene” that had begun to expand across nearby London, and featured bands such as Kilburn and the High Roads and Brinsley Schwarz which like Dr Feelgood employed a similarly raw and exuberant sound. Dr Feelgood signed to United Artists in 1974 and released two albums the following year, ‘Down by the Jetty’ and ‘Malpractice’. With their popularity mushrooming, their next album, a 1976 live record ‘Stupidity’, shot straight to number one in the UK charts, being the first live album to do so in the first week of its release, and remaining there for the next eight weeks. Dr Feelgood’s time in the spotlight was, however, just fleeting. Brilleaux and Johnson’s relationship had become volatile, and, although Johnson was the songwriter in the band, during the sessions for their 1977 next album ‘Sneakin’ Suspicion’, he was fired. Dr Feelgood would go on to have a Top 10 chart hit in early 1979 with ‘Milk and Alcohol’, but without Johnson although remaining a powerful live draw were never able to maintain the same dynamism. They continue to play together today in a very different line-up, although Lee Brilleaux died of cancer at the age of 41 in 1994 and both Sparks and the Big Figure left the group in the early 1980’s. Wilko Johnson spent three years fronting a band called the Solid Sensers, which had a self-titled album in 1978, before joining Ian Dury and the Blockheads in 1980, replacing guitarist Chaz Jankel. Johnson appeared on the Blockheads’ third and final album, ‘Laughter’, before they went into a long hiatus, finally returning in the mid 90’s with Jankel back on board. Since 1985 Wilko Johnson has fronted his own trio, the Wilko Johnson Band, which also features bassist Norman Watt-Roy and drummer Dylan Howe, both of whom are also in the Blockheads. Wilko Johnson is currently touring Britain with the Wilko Johnson Band in a tour that they have labelled the ‘Oil City Confidential Tour’. Pennyblackmusic spoke to him about the documentary, his new career as an actor and Dr Feelgood. PB: Dr Feelgood are seen as the missing link between blues and rock ‘n’ roll at one level and punk at the other. Until recently, however, they were often missed out of the history books. Were you surprised when Julian Temple first got in touch with you wanting to make a film about the band? WJ: I was very surprised. Not only that, but I was sure that it was impossible. We existed in the day before video cameras. There was very little footage or so I thought available, but of course he stitched it all together (Laughs). PB: The footage in the film of Dr Feelgood playing a gig at the Kursaal in Southend is already well known, but there is other footage of an early jug band that you were in and at a rock ‘n’ roll concert at Wembley in which Dr Feelgood were the backing band to Heinz Burt from the 60’s group the Tornadoes that is less well known. Where did he dig some of that footage up from? WJ: Julian and his people were constantly trying to give me the third degree and to get me to remember things. I think that I remembered most of the things in it in the end. There was one bit in the film where the band is sitting by a lake and being interviewed. I am sitting there like a sulky, big rock star, sneering away (Laughs). I have never seen that before. I don’t know where they found that. There is also a bit in the film from a television documentary in which you see me kicking off at plans to extend the number of oil refineries near Canvey Island. They found their own way to that too. PB: The film is as much about Canvey Island as it is about Dr Feelgood. It is almost the unofficial main character of the film. Was that Julian’s idea from the beginning to make Canvey Island as important a part of the film as Dr Feelgood? WJ: From what I have seen of him working I think he develops his ideas as he goes along with what there is to hand. Whether he intended that at the beginning I don’t know. It is funny though. In the way he patched the story of the band together, I would say that he gave a particularly accurate and truthful account and conveyed well the atmosphere of what it was like to live in Canvey Island in the early 1970s. PB: Coming from Canvey Island obviously gave the band a lot of its identity and uniqueness. Many groups who are into the blues look to the Mississippi Delta for their inspiration and often create a fantasy world for themselves based around that. Dr Feelgood never did that, preferring to focus on the fact that it was from Canvey Island. Was it really early on in Dr Feelgood’s history that you realised that Canvey Island has its own sense of myth and character? WJ: When we first started, we were like every other local band. We had a gig every two or three weeks and would spend a lot of the rest of the time sitting around and fantasising and imagining what we would do if we became successful. We started having these fantasies about Buick cars and cheap suits and realised that the place where we lived fitted that whole kind of idea perfectly. PB: You broke out into the pub circuit in London and started playing places like the Lord Nelson and Dingwalls. If you had just remained on Canvey Island, do you think that you would have lasted long or would have just petered out after a couple of years? WJ: We would have certainly broken up Local bands are like that. We started the band after Lee Brilleaux and I had a chance meeting. I bumped into him in the street and we started talking. I actually hadn’t played my guitar for about four years at that stage. I stuck it under my bed when I went to university and I just didn’t play it again. You get a band together to have fun playing music and it is pretty kind of haphazard what happens after that. It couldn’t possibly have lasted if we had stayed on Canvey Island. We took another step when we started playing in London. PB: How well did you and the other members of the group know each other before you formed the band? WJ: All of us were from Canvey Island. In fact The Big Figure and I are more or less exact contemporaries. We were more or less born around the corner from each other. We’d known each other all our lives. Lee and Sparko were four or five years younger. Before I went to the university I had a jug band with my brother and we used to play on the street. One day Lee and Sparko came walking along and they were just little boys to us. We were about eighteen and they were about fourteen or something and they were very curious about this music. I remember Lee because his personality was so vivid and I would see him and Sparko quite a lot after that. They started playing music together not long after that. Figure and I were also in several bands before we formed Dr Feelgood. PB: How long did it take you to realise that Dr Feelgood had a magic together on stage? WJ: (Laughs) I have some cassette recordings of our very early gigs. Now when I listen to them, they sound atrocious (Laughs). We sounded totally amateurish, but I know that even then at the time those recordings were made I was starting to think that there was something about this band. I knew that it was pretty ropy musically, but there was just something about it which I think largely radiated from Lee Brilleaux. PB: Dr Feelgood were precursors to the punks. On the sleevenotes to the DVD of ‘Oil City Confidential’ Julian Temple describes you as being “John the Baptist to Johnny Rotten’s Anti-Christ.” How much contact did you have with the punks and how did you get on with them? WJ: My first inkling of them was one evening I was at home and Dave Higgs, who founded Eddie and the Hot Rods, came around. He was saying that they had had this really bad support act and they were called the Sex Pistols. I thought, “What a fucking great name for a band” and then I thought no more of it until a short time later I was in New York and I acquired a copy of ‘The Daily Mirror’ and on the front there was the whole Bill Grundy thing. I was like, “The Sex Pistols. That’s that band that Higgsy was talking about” (Laughs). When the punk thing first started happening in London, we were touring America a lot and then shortly after the band broke up. When that happened, I didn’t know these people and what their attitude to me would be, but immediately afterwards I started meeting them and they were all fine to me, which was quite nice really (Laughs). PB: Vic Maile who produced ‘Down by the Jetty’ and ‘Malpractice’ went on to produce other acts who had a very similar rough-edged sound such as Motorhead and the Godfathers. How much do you think he brought to those recordings and how much of an influence did you end up having on him? WJ: Vic Maile was a great guy, but on that first Feelgoods album I was completely obsessed with my way of looking at things (Laughs). For instance I wanted to record an album that was like the kind of music that I got off on originally. I refused to do any overdubs on it at all. It was recorded live in the studio, bang just like that. Multi-track recording was just getting into vogue then and it had become standard for a band to go into a recording studio. You would start the thing off with the drummer and the bass player going at it together and cranking out a rhythm line and then putting a guitar on top. I didn’t want to do it like that. I thought it was a terrible idea. As a result of that, I started clashing with the record company. Vic Maile wanted to do what the record company wanted which was produce a record like records were supposed to sound at that particular place in time. There are lots and lots and lots of things that Vic put into it, but you couldn’t actually pick them out. He was a very nice, but timid guy and there was me never having been in a studio in my life and laying down the law about how to do it(Laughs) and him really worried about what the A and R people were going to say if turned up with thing the way I wanted it. ‘Down by the Jetty’ was Vic’s first job as a producer, but he had made a name for himself as a live recording engineer. In fact he had recorded ‘The Who Live At Leeds’ and so he had developed a reputation for that kind of work. That was why the record company looked to him to produce ‘Down at the Jetty’ because it was a kind of live record, although of course they didn’t really want a live record (Laughs). As a result of him producing Dr Feelgood’s album and, as we were a band that was happening at that time, that is the sort of work he ended up doing. PB: ‘Stupidity’ was the first album to get to number one. It was the first live album ever to get to number one in the week of its release. Did you expect it to do as well as it did? WJ: We had been building up and touring and so forth and ‘Down by the Jetty’ did reasonably well and ‘Malpractice’ did even better and so a live album was something that was looked for. It was expected to do fairly well, but when it went to number one it was very gratifying to me for several reasons (Laughs). PB: One of those was that it involved all live takes? WJ: Yes. PB: What were the other reasons? WJ: Well, again with ‘Stupidity’ I got into an eyeball to eyeball thing with the record company. We’d got these live takes and I said, “Well, we’ll just go ahead and mix them and if there are bum notes we’re not mucking around with it.” Again if you bought a live album, you would probably end up on the actual record just hearing the bass drum track or something like that and everything else would be done in the studio. I just didn’t want to do that. At one point the A and R people were saying that they wanted Figure to overdub every single snare drum beat just to get the sound they wanted and I was like, “No, no. When people come to see us, this is it. This is what happens and they seem to like it. I think that this is what they would want.” Anyway it did end up with me more or less telling the A and R guy to get out of the studio as we were doing it this way. Vic Maile told me that he went to Vic and said, “Listen. I am going to let Wilko have his way on this one. This record is going to flop and then he’ll have to do as he is told.” That was another reason why it was very gratifying. PB: Your and Lee Brilleaux’s relationship became acrimonious, but if you look at the footage of the Southend gig which was shot not that long before you left the band there is this real spark of electricity and adrenalin between you on stage. Did the acrimony stop at the stage door? WJ: We never took any of that rubbish on stage with us. People don’t come to see you sulking or shouting at each other. They come to see the whole thing and also the whole nature of performing has always been to me and particularly in that band was that you have to absorb yourself in it and absolutely all you’re thinking of is the performance. A couple of times Lee and I were having these screaming rows or scenes and then the gig would go really well and then afterwards people would say, “You two do that to each other deliberately to wind each other up” and I would go, “No. Really, we don’t (Laughs). When the film was shown for the first time, that was the first time I had seen that footage actually, and, oh man, it gave me some memories I tell you of what it felt like being on stage with Lee. PB: How much contact did you have with Lee after you left the group? WJ: None. PB: After that you became involved with the Blockheads. Is it true that Ian Dury invited you to join the band without consulting with the rest of the group? WJ: It’s true (Laughs). Having got to know subsequently what life was like in the Blockheads, I would imagine that there was some kind of row about it. There was in everything that they did I think. I knew Ian and Davy Payne, who is the saxophonist, from Kilburn and the High Roads. I didn’t know the other guys in the Blockheads, but I thought they were a great band and especially their bass player, Norman Watt-Roy. One of the strong reasons for wanting to play with them was to play with him. It’s all been a big thirty year plot to get him into my band (Laughs). PB: And it has obviously worked successfully because he has played with you in the Wilko Johnson Band since 1985. How easy has it been for him to do that with his other commitments to the Blockheads who are still an active outfit? WJ: When Ian was still alive, we had this arrangement that, because Ian only went on the road and did things sporadically, that if he ever wanted to do anything I absolutely rearranged everything so that Norman could play with him and vice versa. Since Ian died, that hasn’t happened so much. We have now got Dylan Howe, the drummer from the Blockheads, in the Wilko Johnson Band as well. Mickey Gallagher (the Blockheads' keyboardist and leader since Dury's death-Ed)must hate me (Laughs), but we just try to arrange things so that if the Blockheads want to do a tour we fit around each other. PB: You were in the Blockheads for about two years. ‘Laughter’ is a very dark album and Ian Dury was apparently in a pretty bad way at the time that he was making it. Was the experience of making that album good or bad as a whole? WJ: It was good for me. I was just stepping into something completely new both in the people I was working with and the kind of music that I was playing. It was at a time when I was down in the dumps, which is pretty much where I normally am (Laughs), and it got me out of it. A lot of it was really enjoyable for me, especially going on stage at some of the really big gigs. I was in the rhythm section. Ian was down the front. He was the one that had to worry as all the attention was on him. It was a great thing. PB: Last few questions. Is it true that you have recently signed up to play an executioner in a children’s programme? WJ: Well, that is what I thought that I had done, but what has actually happened is that I have found myself taking part in this big film production for HBO. There’s a book called ‘Game of Thrones’ which is one of these fantasy books and it’s a particularly ferocious one. It has been a bestseller and HBO are making what I think is a ten part series starring Sean Bean. It is knights in armour and swords and not a children’s thing at all. It is a bit gruesome really and the character I play is an extremely unpleasant fellow. The one great thing about him though is that he has had his tongue cut out, so I don’t have to learn lines. All I have to do is wander around and give people dirty looks. When they asked me, I said, “Yeah. I can do that all day long” (Laughs) PB: Had you done any acting before? WJ: No. Never. PB: How did you get the job? WJ: I believe that Julian Temple mentioned my name. They were looking for somebody to play the character who looked similar to me. I did some filming in Belfast last month and I am going to Malta next week for a week or so. It doesn’t actually start at the beginning and end at the end, so what is actually going down I don’t really know, but if they want me out there for a few days I am bound to be doing something, aren’t I? I’ll be hacking people to pieces and stuff (Laughs). It has been terrific fun. PB: You’re also doing the ‘Oil City Confidential’ tour as well at the moment with the Wilko Johnson Band. What is the sort of thing that people can expect from your set? Is it going to be Dr Feelgood songs, Blockheads songs, your own songs or a mixture of all of them? WJ: The sets I play are usually my songs, which then include some Dr Feelgood songs, ‘Back in the Night’ and stuff like that. Although I am outnumbered by Blockheads- In fact we are all Blockheads, aren’t we? -we don’t go down that road at all. I leave them to do that with the Blockheads. What I do is very, very simple. It is skiffle. I have got two superb guys playing behind me. I can stop playing and wave my arms about and it would still sound good (Laughs). PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/WilkoJohnsonBand/http://wilkojohnson.com/

https://twitter.com/wilkojohnson

Picture Gallery:-

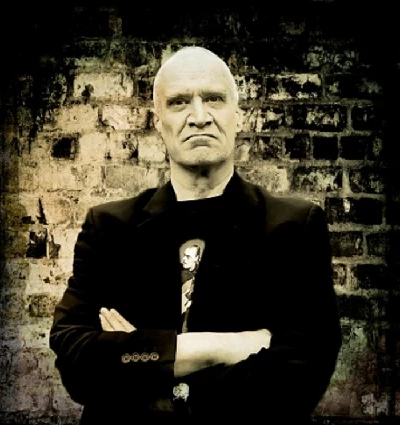

intro

Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson talks to John Clarkson about his former band, his new acting career and 'Oil City Confidential', the recent Julien Temple documentary film, about them

interviews |

|

Interview (2012) |

|

| John Clarkson speaks to guitarist Wilko Johnson about his years with influential 70's band Dr Feelgood and forthcoming autobiography, 'Looking Back At Me' |

reviews |

|

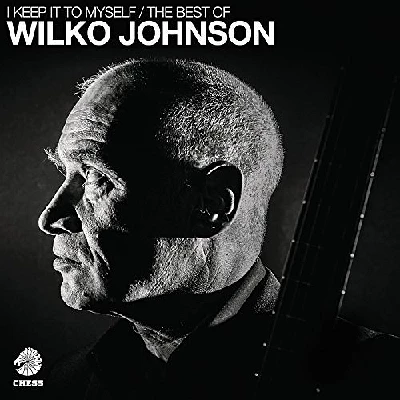

I Keep It to Myself: The Best of Wilko Johnson (2017) |

|

| Fabulous double CD best of compilation from former Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson, which consists of songs from his catalogue which he re-recorded between 2008 and 2012 |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart