Miscellaneous - The Berlin Albums of David Bowie and Iggy Pop

by Jon Rogers

published: 27 / 8 / 2009

intro

Inn our 'Soundtrack of Our Lives' column, in which our writers reflect upon music that has had a personal impact on them, Jon Rogers examines the mid 1970s Berlin albums of David Bowie and Iggy Pop

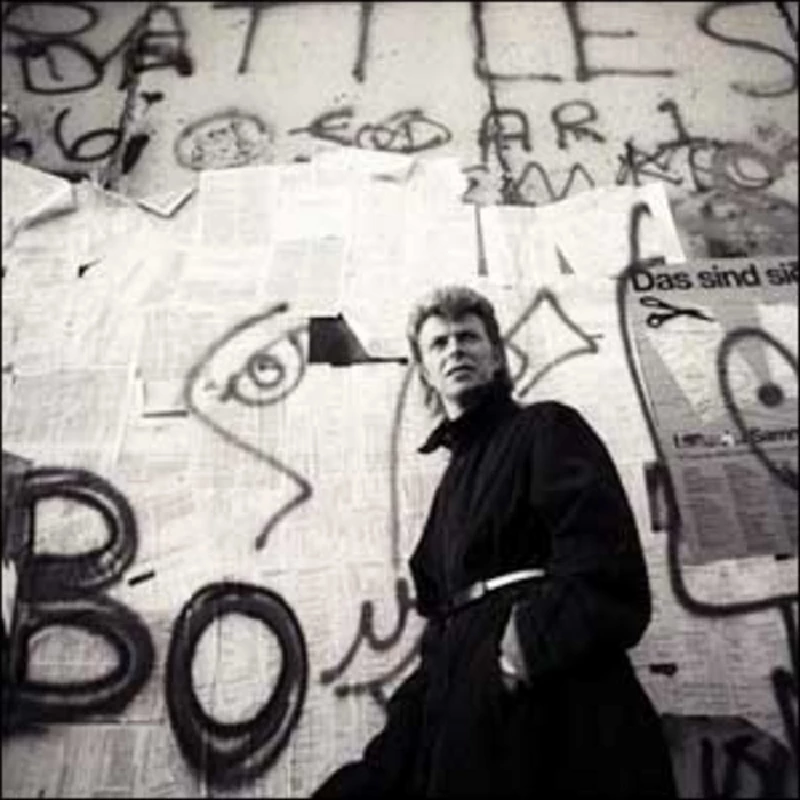

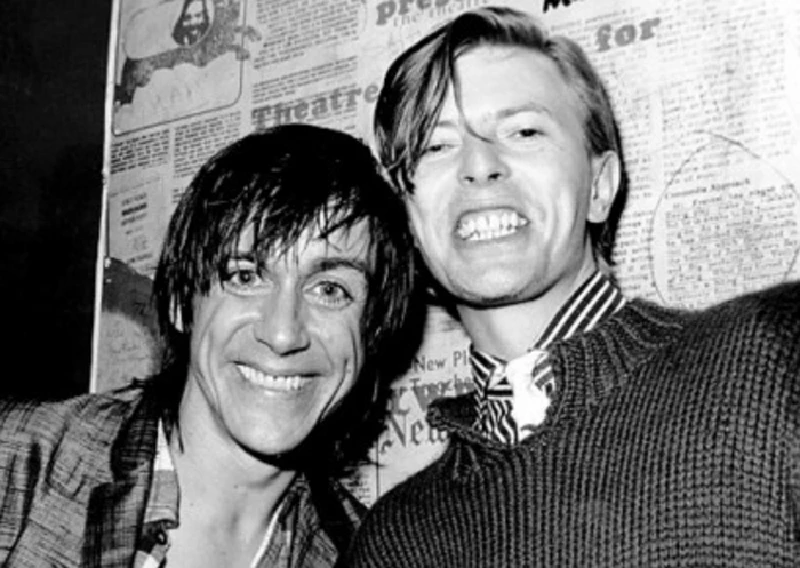

Berlin in the early 70s wasn’t the place it is today. It was still devastated from being bombed and ransacked during World War II and then as the Cold War set in it had been divided up between the West, controlled by the Allies, and the East, which was in the hands of the Soviet Union. A grey, sombre atmosphere seeped into everything as well as an uneasy, unsettling almost paranoid sense encroached on everything. As a counterpoint to this austerity West Berlin also had its decadent, self-indulgent side where people could indulge their vices – often with detrimental effects – of all descriptions. It was, effectively, a land-locked capitalist city surrounded by a socialist state. Former Velvet Underground front man Lou Reed once said of the place, “Berlin is a divided city and a lot of potentially violent things go on there [...] It reminds me of Von Stroheim and Dietrich.” But even before Reed knew much about the German city he’d used the backdrop of Berlin for one of his most bleak and harrowing albums. Despite the name, 'Berlin' was actually recorded in the less dramatic setting of Willesden in North West London. The song cycle told the disturbing tale of a doomed romance between an expatriate American prostitute and a German drug addict and colouring the album an even further darker shade of black was the effect on Reed of the suicide of Andrea Whips (aka Andrea Feldman), who had starred in Andy Warhol’s film Heat and was part of the Factory crowd. On the album the main female character Caroline ends up taking her own life. Reed’s “old lady” Bettye, his first wife, also tried to kill herself during the recording of the album. He told Allan Jones once: “She tried to commit suicide in the bathtub at the hotel. Cut her wrists, she lived. But we had to have a roadie there with her from then on.” Their faltering relationship effectively came to an end after the recording had finished when he kicked her out saying he wanted to “make a fresh start”. The theme of the album also took its toll on producer Bob Ezrin who recalled about the sessions in 1976, “We killed ourselves psychologically on that album. We went so far into it that it was kinda hard to get out.” Talking to Nick Kent in 1974 Reed argued, “I had to do 'Berlin'. If I hadn’t done it, I’d have gone crazy. If I hadn’t got it out of my hair, I would have exploded. It was a very painful album to make. I don’t wanna go through that again, having to say those words over and over and over.” The album clearly hit a nerve with Reed and meant a lot more to him than his previous eponymous and 'Transformer' albums. “The way that album was overlooked was probably the biggest disappointment I ever faced,” Reed said in 1977. “I pulled the blinds shut at that point.” The blinds effectively manifested themselves in Reed’s next persona, his 'Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal' – a skinny, leather-clad rocker, caked in white powder and dangerous levels of speed in his body. On stage he mixed up the rock clichés of a mincing Mick Jagger, the glam of Bowie and Ronson as well as the theatrics of Iggy Pop as well as sending up the likes of female screen icons like Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield. Musically, songs like 'Rock ‘n’ Roll' and 'Waiting for the Man' were stripped of their subtleties and given a hard rock sheen which some critics viewed as “blasphemous”. There was also an uglier side to Reed’s latest persona. Along with the austere, brutal look, Reed’s hair had been shaved into an austere crew cut with Maltese crosses dyed in. The symbol associated with the German Reich and used on von Richtofen’s airplanes in the First World War were also associated to many with Nazi Germany and the swastika. Even Reed’s management had reservations. Reed’s consumption of excessive amounts of amphetamines along with his skinny, deathly pallor observers had him pegged as the next rock star to self-destruct. While many came to Reed’s shows out of a mawkish hope that the one-time Velvet Underground would shake off his mortal coil live on stage and felt that he walked into a creative cul-de-sac there was one important supporter and long-term fan: David Bowie. The two first met when Bowie was on the cusp of superstardom and had flown to New York to sign his RCA deal. The record company, which was also home to Reed, set up a dinner at the Ginger Man. Along with Bowie and Reed were Angie Bowie, Mick Ronson and assorted record company executives like Dennis Katz. After the meal the party moved on to Max’s Kansas City where Bowie and Reed met up with another pivotal character at the time, Iggy Pop. Bowie was certainly in awe of Reed at the time and told 'Rolling Stone',“Lou Reed is the most important person in rock and roll in America.” But, according to Angie Bowie he might have had more cynical reasons for associating with Reed. “David was very smart. He’d been evaluating the market for his work, calculating his moves and monitoring his competition. And his only really serious competition in his market niche, he’d concluded, consisted of Lou Reed and maybe Iggy Pop. So what did David do? He co-opted them. He bought them into his circle.” The height of the pairing resulted in Reed’s acclaimed album 'Transformer', which Bowie produced. Bowie had also befriended the former Stooges singer Iggy Pop in 1970s and became close. According to David Buckley’s biography of Bowie the English singer was the only person to visit Pop when he checked himself into a psychiatric hospital in 1975. Bowie rejected the traditional gift of a bunch of grapes in favour of drugs to help cheer the American up. The two stars had very different on stage personas. Pop was still “the street walking cheetah with a handful of napalm.” Drawing on the shamanic tradition, Pop could invariably be seen on stage, stripped to the waist, usually self-mutilating with cut glass or whatever could be found and invariably goading the audience to react. And he wasn’t shy of getting his manhood out either if the feeling grabbed him. Bowie on the other hand was much more clean cut and carried an air of artistic aloofness with him. Bowie would perhaps come to embody the whole essence of Berlin at the time with what would become known as his Berlin trilogy of 'Low', 'Heroes' and 'Lodger' and inextricably linked to all three would be Bowie’s producer, Brian Eno. Although Bowie had set up base in Berlin, along with Pop, in 1976 he’d decamped to the Chateau d’Hérouville studio in Pontoise, a North West suburb of Paris to work on a new album. His career had effectively stalled. After the number one hit 'Fame' and the “plastic soul” of 1976's' Station to Station' he’d been exhausted by a world tour and leading an LA lifestyle, where he developed a $300-a-day cocaine habit. His weight had fallen to under seven stone and he was living on a diet of red and green peppers, washed down with milk straight from the carton. Not only that he’d been researching the work of occultist Aleister Crowley and become convinced he was being followed by witches. He started keeping his urine bottled up in the fridge in order to stop evil spirits getting it. Moving to Europe was part of the strategy to clean up but also along for the ride was Iggy Pop, also hoping to clean himself up after years of self abuse as a member of the Stooges. The main reason to go to the French studio was for Pop to record his debut solo album, which would ultimately become 'The Idiot' and contain the classic 'Nightclubbing'. But the sessions were all wrapped up by August and the pair stayed on to work on Bowie material with Pop taking up the role of studio mascot. 'The Idio't recordings would then be finalised in the Musicland Studios in Munich and then the Hansa Studios in Berlin. The basis for 'Low' were the outtakes and rejects from Bowie’s work the previous year for the soundtrack to 'The Man Who Fell to Earth', but after a row with the producers Bowie withdrew taking the music with him. Now he set about revisiting the unfinished work. Eno, who had just finished producing the debut album by Ultravox was roped to twiddle the knobs. Like Bowie, Eno was at the time currently inspired by the current wave of experimental German bands –collectively known as krautrock – from the likes of Kraftwerk, Neu!, Can and Harmonia that perhaps weren’t too far removed from the work Eno had done with Robert Fripp a few years back. By the time Eno arrived basic sketches had been worked up into songs with Bowie promising it to be “the first album for the future” and it had the working title of 'New Music Night and Day'. The name was eventually changed to 'Low' to pun on the phrase low-profile where the cover had a profile picture of Bowie. Working with Tony Visconti, Eno was initially there to help with overdubbing and to add Discreet Music-style synthetic textures to the tracks but his role soon took on a much more significant turn. Whilst Bowie had to go to a Paris court to attend proceedings against his one time manager Michael Lippman. Eno remained in the studio, slowly working on the key instrumental track 'Warszawa' (inspired by Bowie’s trip to the Polish capital and hearing a children’s choir there) and 'Art Decade', with Eno adding spectral overdubs to the latter. 'Weeping Wall' and 'Subterraneans' were also given a makeover. Effectively the second side of 'Low,' largely instrumental, was a collaboration between Eno and Bowie although Eno would only get credit for 'Warszawa' where Eno added the Gothic atmosphere. Eno told 'Punk' magazine, “It’s a very slow, melancholy piece that’s rather like a kind melancholy. Very nice.” Bowie, taking his cue from Neu!’s album 'Neu! ’75', where the two sides of the album were labelled 'Night' and 'Day' respectively would use vastly different styles for the two sides of 'Low'. Up first were seven relatively straight forward, short pop songs, while side two was reserved for the longer, drum-less instrumentals Eno had worked on. Initially RCA wasn’t too happy about the record and thought it amounted to commercial suicide but that opinion quickly changed when 'Sound and Vision' was released as a single and became Bowie’s biggest hit since 'Space Oddity'. Critics remained wary either praising its avant garde credentials or appearing to be dumbstruck at his apparent rejection of his previous commercial success. Fans didn’t have such reservations with 'Low' reaching No. 2 in the UK and No. 11 in the USA and it helped secure Bowie’s art-rock credentials and with the album’s release coming just a few months before the outpouring of punk and its ‘year zero’ attitude it helped Bowie from being viewed by them as a musical dinosaur. In fact the album was a huge influence on many post-punk bands like Wire and Magazine. And even an early version of Joy Division used the name Warsaw in tribute to the 'Low' track. After the initial tracks for 'Low' had been recorded Bowie and Visconti moved back to Berlin to mix the album at Die Hansa Tonstudio on Köthenerstrasse. Bowie and Pop moved into a rent apartment at 155 Hauptstrasse , over a car shop, in the city’s Turkish Schöneberg district, not far from the studio. The pair were also cleaning themselves up – to some extent – and spent the afternoons painting or food shopping. While tales of cocaine use still circulated, their main vice was lager which they consumed in vast quantities. When Bowie wasn’t recording he was often touring the city by bicycle, visiting the Brucke Museum and wandering round Kreuzberg, the gay area of the city. According to a feature in 'The Independent' in 1991 friends remember Bowie also being very interested in everything to do with the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. While both Bowie and Pop might have been on the road to recovery they were far from the finishing line. Bowie collapsed in the flat one day and it’s suspected this was either due to an overdose or a severe anxiety attack. Or simply from just having too much to drink. Pop’s own clean-up programme wasn’t going well either. Speaking in 1999 Pop said that during those days they both would be “good boys” for most of the week but then “binge for two days”. While Bowie was putting the finishing touches to Low Pop was busy on his follow up to 'The Idiot', 'Lust for Life' which Bowie was producing with Colin Thurston. The contrast between the two albums was immediate. 'The Idiot' was louche, dark and brooding and featured a skinny, pale Pop on the cover in monochrome black and white. And the music reflected that. 'Lust for Life' though, while still using a black and white picture of Pop, had the singer looking healthier with a big, impish grin across his face and songs like 'The Passenger' and the title track bounced along with a new joie de vivre. According to Pop the title track was written by Bowie on a ukulele: “He cribbed the rhythm of this army forces network theme, which was a guy tapping out the beat on a Morse code key. Ever the sharp mimic, David picked up the nearest available instrument and started strumming.” And like 'Low', 'Lust for Life' was recorded at Hansa as was Bowie’s next album 'Heroes'. Reminders of the Nazi reign were conspicuous at Hansa with the cavernous Studio 2, where 'Heroes'was recorded, had once been a grand ballroom and had been used by the Gestapo during the war. As well, looking out from the studio you could see the site for Hiter’s final hideout, the Führerbunker. Not only that the dividing Wall between east and west was only a few hundred metres away. One East German guard could see right into the studio itself. The big, cavernous dimensions to the studio helped give the album its spacial ambience and two microphones were slung 50 feet up in the air to capture that quality. Along with the experimental side to the album both Eno and Bowie were in good moods spending a lot of the time just laughing. “We spent most of our time joking. Laughing and falling on the floor,” said Bowie later in 1977. “I think out of all the time we spent recording, 40 minutes out of every hour was spent just crying with laughter.” The two, according to Eno would take on characters that they played, loosely based on Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. Work was still getting done though as the songs all evolved in the studio, except for 'Sons of the Silent Age' which Bowie had written before recording had even started. The songs though were all first takes. Second takes were done but, according to Eno, not as good. One unlikely influence on the record was Eno’s current obsession with Donna Summer’s disco hit 'I Feel Love' which he constantly played. Eno thought the song’s marriage of a pulsating rhythm with lusty sensuality, thanks to Gorgio Moroder’s slick production, lay the building blocks for a new club music. Randomness also played its, conscious, part. Bowie had been a fan of US Beat writer William S Burroughs for some time and used the author’s cut-up technique to good effect on 'Diamond Dogs', where text would literally be cut-up and then rearranged to create a completely different meaning. Bowie and Eno drew on this idea at Hansa. If the pair were stuck finishing a song they would consult random cards they had placed around the studio on which they had written a variety of recording techniques or devices. Some songs, like the instrumental 'Sense of Doubt', were almost entirely constructed by using these cards. Either Bowie would turn over a card and without telling the other what it said adhere to its advice. “It was like a game,” said Eno at the time. “We took turns working on it; he’d do one overdub and I’d do the next.” The two would also work closely on the co-authored Neuköln as Eno added a misty synth texture to Bowie’s saxophone solo, evoking cold, wintry nights and dim-lit city streets. Eno collaborator Robert Fripp was also drafted in to help with the sessions and a jet-lagged Fripp turned up straight from the airport. “I was completely out of my brain,” Fripp later confessed. “I didn’t know whether I was coming or going. I just went in and did it.” Listening to what would become 'Beauty and the Beast' Fripp set up his Les Paul guitar and started idly playing along. Eno quickly filtered it through a variety of synths and effects and started to record. Fripp would keep this up for another six hours with nearly all of his first takes being used. Having left a marked impression on the album Fripp simply packed up his stuff and flew back to London less than 48 hours after arriving. Fripp’s most significant work was on the title track itself which had begun life as an orthodox 4/4 rhythm drawing on Neu!’s track 'Hero' and the Beach Boys’ 'Marcella' as well as Kraftwerk’s 'Trans Europe Express'. According to David Sheppard’s biography of Eno, 'On Some Faraway Beach', Bowie’s lyrics were inspired not by two Berliners meeting for a tryst, as was explained at the time, but by Bowie seeing Visconti in a clinch with the German backing singer Antonia Maass. Visconti at the time was still married to Mary Hopkins. Sessions for the album would often stretch into the early hours and once finished Eno and Bowie would return to Hauptstrasse exhausted where Eno would often devour bowls of wheat flakes and Bowie would, too tired to cook, eat raw eggs. Like 'Low', 'Heroes' was divided in two: a song side and a semi-instrumental side, although this time around there were only three non-vocal tracks. A fourth, 'Abdulmajid,' was also recorded but not originally issued. The track only appeared on the 1991 CD reissue. There may have been lapses into the drugs but Bowie was, generally, on the way to a healthier lifestyle and was living a far less cocooned existence than the one in LA. He told Jean Rook in 'The Daily Express' in 1979, “Every day I get up more nerve, and try to be more normal, and less insulated against real people.” He added “When I thought I was coming to the end of my tether I considered everything as a way out.” Berlin was, oddly, good for him. At the time he commented,“I like the friction. That’s what I look for in any city. West Berlin has the right kind of push. I can’t write in a peaceful atmosphere at all, I’ve nothing to bounce off. I need the terror, whatever it is.” On the third in Bowie’s so-called 'Berlin' trilogy, the singer once again worked closely with Eno, butwas actually rather removed from the German city in both physical location and influence. Bowie had moved back to Switzerland and was set up at the Mountain studio in Montreux. The studio had been made famous thanks to Deep Purple immortalising it in 'Smoke on the Water'. During a Frank Zappa gig at what had been the Montreux Casino, a member of the audience left off a distress flare, setting the place alight. The album that would eventually see the light of day as 'Lodger' had the initial working title of 'Planned Accidents 'and would consist of a song side and an instrumental side. But that plan was quickly shelved once Bowie’s lyric writing got underway. Along with the Germanic motorik pulse developed on 'Low' and 'Heroes', 'Lodger' also contained what Eno, Bowie and Visconti referred to as “hybridism”, effectively what would be called world music nowadays, those ‘ethnic’ influences would be married to a western rock aesthetic. The song 'African Night Fligh't – with its nod to the Walker Brothers – was influenced by some Kenyan singers Bowie had heard on a recent trip to the country with his son. Bowie would use what he termed “Turkish reggae” on 'Yassassin'. These uses of non-western musical styles fitted in with the album’s overall theme of people being tenants, or lodgers, of transience and exile and a rootlessness. A theme that both Bowie and Eno could relate to with both men largely moving between the UK, the USA and Europe at the time. This time though the creative spark between Eno and Bowie just wasn’t the same. Adrian Belew, present at the recordings, noted, “They didn’t quarrel or anything uncivilised like that; they just didn’t seem to have the spark that I imagine they might have had during the 'Heroes' album.” Gone were the comedic Pete ‘n’ Dud role playing. Bowie seemed to be tiring of Eno seemingly endless theoretical approach. During recording Eno would even write up his eight favourite chords on a blackboard, and got the rhythm section to play along with Eno pointing to particular chords with the air of an university professor. The following year Bowie confessed to the 'NME' that “I used to like most of what they [Eno and Fripp] did on their own records a lot, but now have my doubts about all this endless conceptualising.” In the same interview he dismissed Eno’s groundbreaking album 'Music for Airports' as “unremittingly dull.” Eno and Bowie’s working relationship still had legs though, most evident on 'Boys Keep Swinging' which started life as Louis Reed, in tribute to the former Velvet’s singer. The rudimentary punk energy was captured by the musicians all swapping instruments. The androgynous song was released in the UK and gave Bowie his first Top 10 single since February 1977. Once recording was finished Bowie left Switzerland for a tour of Australia and the album would eventually be finished in New York at the Record Plant Studios on West 44th Street. Eno hadn’t been present at the final stages of either 'Low' or 'Heroes' and his presence now led to frictions between himself and Bowie and Visconti. Arguments erupted over minute details about the mix and tempers frayed. Bowie publicly denied any ill feeling and said he would happily work with Eno again, but it would be another 16 years before the two would hook up again. The Berlin-inspired era, if not a high watermark, in the careers of Bowie, Eno, Reed and Pop, it was certainly a creative peak and in the immediate years after all would be, relatively stagnant. Bowie, despite the single 'Ashes to Ashes', stumbled with the 1980 album, 'Scary Monsters and Super Creeps'. Eno couldn’t quite reignite the brilliance of his earlier production work with Talking Heads. Both Reed and Pop spent years putting out sub-standard records. The period may have been overly self-indulgent and narcissistic but also experimental and ground-breaking, producing some enduring records that are still critically applauded now.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart