Miscellaneous - The Roxy Our Story and Rick Poyner (Ed)/Oh So Pretty: Punk in Print 1976-1980

by Adrian Janes

published: 27 / 5 / 2017

intro

Adrian Janes reflects on two new books on 1970's punk, one on the legendary Roxy Club and the other on punk fanzines and writing

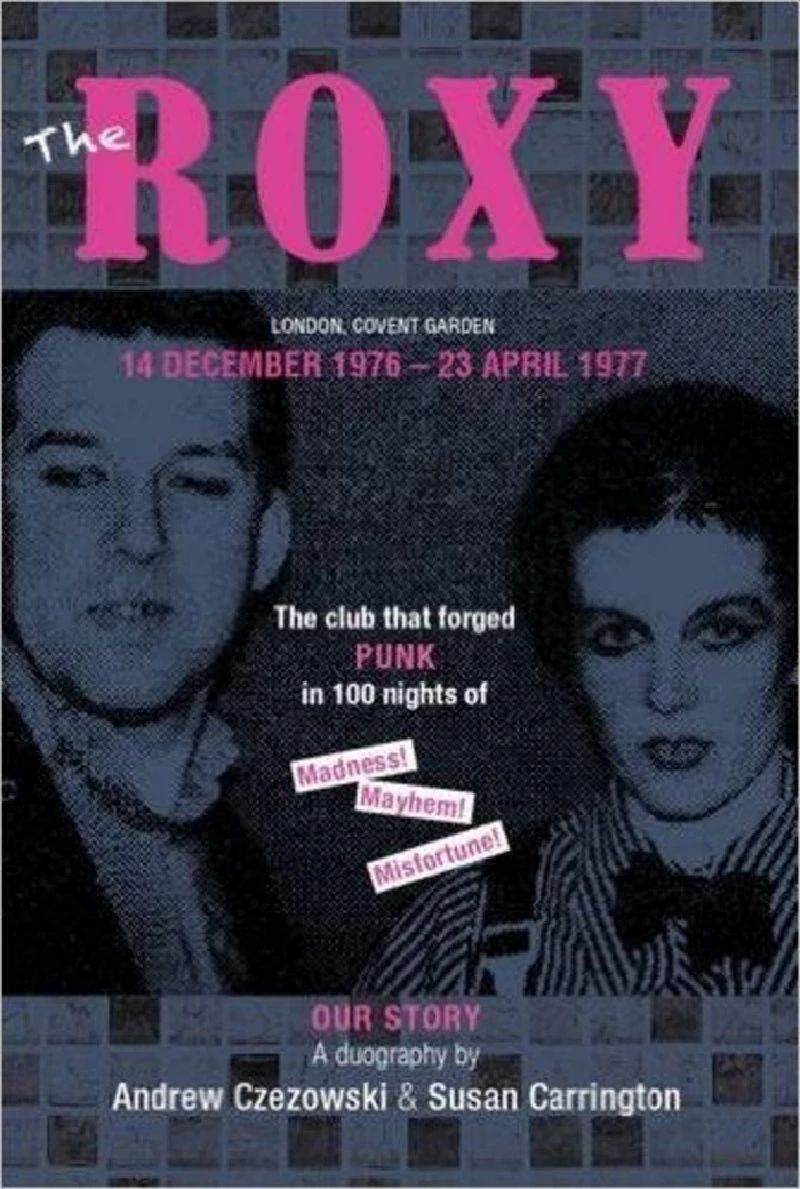

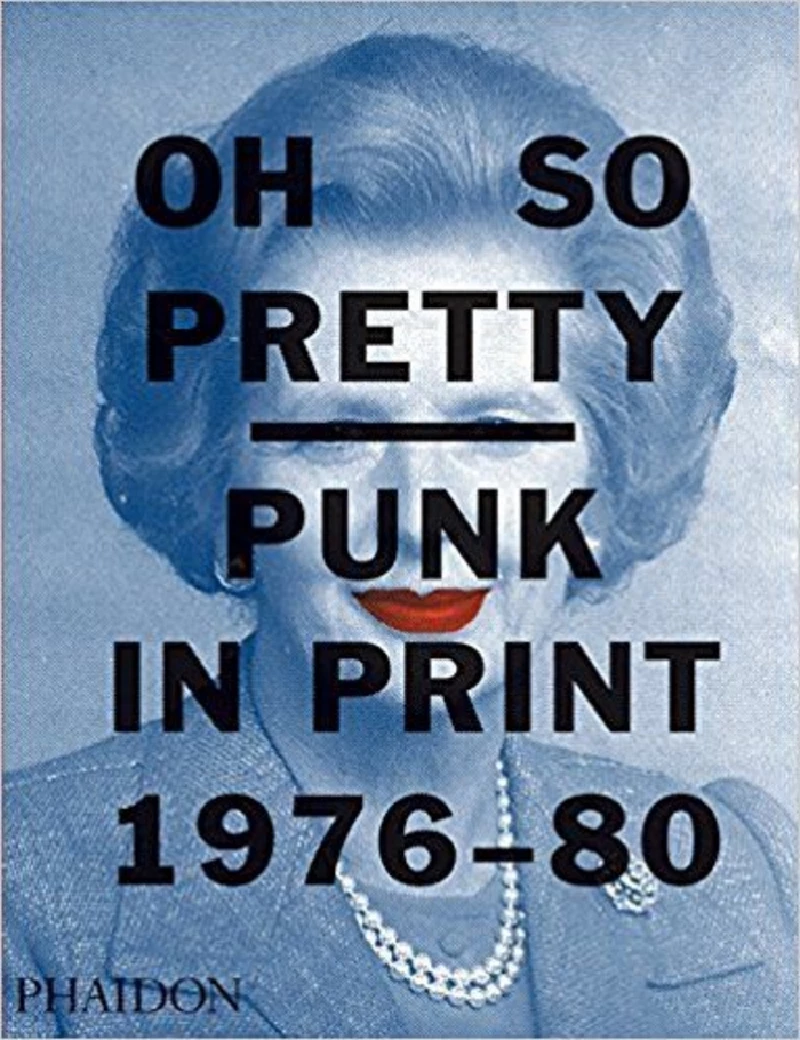

Andrew Czezowski and Susan Carrington: The Roxy Our Story: The Club That Forged Punk in 100 Nights of Madness Mayhem and Misfortune (CorrCzez Publishing, 2016) Oh So Pretty – Punk in Print 1976-80 (Phaidon Press, 2016) These two books both capture something of the vital spirit that ignited punk in Britain. While Czezowski and Carrington’s ‘duography’ is sharply focused on a particular time and place, ‘Oh So Pretty’, a large selection from the extensive archive of Toby Mott, is more of a national overview of fanzines, posters, stickers and other graphics which covers half a decade. Its longer time-span allows it to illustrate the fuller flowering of those seeds of greed, commercialisation and compromise that were already starting to germinate during what Czezowski and Carrington call the Roxy’s “100 nights of Madness! Mayhem! Misfortune!” The club’s story originates in Czezowski’s early involvement with Generation X and the lack of venues for them to play. Becoming aware of a seedy Covent Garden dive for rent called Chaguarama’s, the original idea of taking the place over to showcase Billy Idol and co soon transformed into a bigger idea. This was also to some extent a response to the circumstance (largely created by the Sex Pistols’ reputation, magnified by their December 1976 TV encounter with Bill Grundy) of there being few places for punk bands to play and punks to go. There’s a real sense of energy to the book, thanks to its day by day structure. This is helped by partly drawing upon the authors’ diaries and scrapbooks from the time, along with their later recollections and those of musicians who played at the club (from the archive of music writer Kris Needs), such as Walter Lure (Heartbreakers), Tony James (Generation X) and TV Smith (Adverts). In true punk DIY style there are also several lurid homemade gig flyers. This is all complemented by a number of contemporary music press articles and reviews. It’s worth risking some eye-strain to read these for a glimpse of the time’s attitudes, often as aggressive as the music, for example a classic piece of Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons pontification about everyone they decided was insufficiently rebellious to belong on the scene, grimly hilarious now to anyone who’s followed their respective descents into Christian Zionist and Theresa May fanboy. The headlong speed of the story also mirrors the music. From the hopeful early days of the trial gigs of December 1976 and the Clash appropriately being the band to officially open 1977 (attended by, according to Carrington, “about 400 kids packed into a venue with a capacity of 150”), a falling off of numbers, being robbed of takings, and finally to bitter disputes over rent and booking policy with the landlord. This came to the point in April 1977 where the pair were being sued and were banned from the club they had begun, fortunately not before a live album had been recorded (released on EMI subsidiary Harvest, irony fans). This includes some of the earliest recordings of Roxy bands: talents who have lasted the course (Buzzcocks, Wire); some who had a brief spell in the sun (Adverts, X-Ray Spex); and others who spun off the road entirely (Johnny Moped). The drive that continued to characterise the authors and the punk scene at its best is shown in the conclusion, with the teenage Brixton clubbers of the 1960s they once were later taking over the old Ram Jam club and in 1981 turning it into the renowned Fridge, while club DJ Don Letts made his ‘Punk Rock Movie’ during 1977, the foundation of a stellar career as film-maker and radio personality. ‘Oh So Pretty’ evokes the world in which the Roxy existed, a world of cheaply-produced fanzines, political stickers on lamp-posts, and hoardings with promotional posters that move from imitation of the fanzines’ crudity to increasing colour and sophistication. It’s a movement like that of the music, which went from the monochrome of basic punk to the gradual inclusion of both more adventurous tones and toning things down, as bands followed the roads to New Wave, post-punk and even power pop. At over 500 pages, there does seem to be room for confusion and loss of definition from what the title promises. It’s surely more than a stretch to describe inclusions such as the Tom Robinson Band, Ian Dury, Deaf School and Ultravox as punk, even if they might have might have been affected by the revolution going on around them and had punks among their fans. The book is arranged chronologically, so it’s possible to see the emergence of artists like this mixed in with the fanzines and promotional material for those I’d consider the real definers of punk style and attitude, such as the Pistols, Clash and Damned. Jamie Reid’s work with the Pistols, for example, remains an acridly smoking gun, even if innovations like their ‘ransom note’ logo were soon to be watered down in the same way as punk fashion was made safe for the high street. But rather than getting hung up on the title, it’s probably better to take this book as a visual tour around late 1970s and early 1980s British music and society. On that level, punk fanzines like ‘Sniffin’ Glue’, ‘Ripped & Torn’ and ‘More On’, and collages of fiery photos and words for gig flyers, are revealed as critical but not the only ingredients of what was going on. Politically it was a time when extremes of Right and Left had more of a presence, visible here in arrays of National Front and Socialist Workers Party stickers and dramatic posters for Rock Against Racism by David King. Even before 1977 was over some of the leading lights of the punk scene were already proclaiming it to be finished, as were commentators like Jon Savage (several pages of whose curious fanzine-style collaboration with artist Linder Sterling, ‘The Secret Public’, are reproduced here). In the end, the template of punk music (fast, concise, caustic) was an important corrective but could not restrain for long those musicians who possessed real imagination and ambition. The visual equivalent, such as handwritten flyers, survive beyond that year but also come to be supplanted by more considered but still powerful techniques like the stencils and logo of Crass. On the critical side, there are many occasions when the note beneath a fanzine’s cover pointlessly repeats what you have already just read on that cover. This is all the more irritating, when just as many examples exist of interesting snippets of information being given. On the other hand, it’s a particularly well-indexed book, though for some reason the Roxy is listed as the Roxy Theatre – if Czezowski and Carrington’s book tells us anything, it’s that it wasn’t that grand an establishment. Yet there does remain something grand about the release of creativity, the encouragement to get up on a stage or make a record (given to both men and women – Siouxsie, Poly Styrene and the Slits are well represented in both these books) and the musical cross-pollination that saw Letts spinning dub in a punk club, white musicians adopting reggae rhythms and bands like Steel Pulse appearing at RAR concerts. If we live in an era which still types bands as ‘post-punk’, that in itself acknowledges the punk spirit’s continuing presence.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Screamin' Cheetah Wheelies - Sala Apolo, Barcelona, 29/11/2023 and La Paqui, Madrid, 30/11/2023Anthony Phillips - Interview

Difford and Tilbrook - Difford and Tilbrook

Rain Parade - Interview

Oldfield Youth Club - Interview

Autumn 1904 - Interview

Shaw's Trailer Park - Interview

Cafe No. 9, Sheffield and Grass Roots Venues - Comment

Pete Berwick - ‘Too Wild to Tame’: The story of the Boyzz:

Chris Hludzik - Vinyl Stories

previous editions

Microdisney - The Clock Comes Down the StairsWorld Party - Interview

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Michael Lindsay Hogg - Interview

Ain't That Always The Way - Alan Horne After The Sound of Young Scotland 2

World Party - Interview with Karl Wallinger

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

Steve Harley - Interview

Prisoners - Interview

Barrie Barlow - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Marika Hackman - Big SighSerious Sam Barrett - A Drop of the Morning Dew

Rod Stewart and Jools Holland - Swing Fever

Loves - True Love: The Most of The Loves

Ian M Bailey - We Live in Strange Times

Paul McCartney and Wings - Band on the Run

Autumn 1904 - Tales of Innocence

Roberta Flack - Lost Takes

Banter - Heroes

Posey Hill - No Clear Place to Fall

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart