Miscellaneous - Resistance through Style

by Adam Wood

published: 18 / 5 / 2007

intro

In the second part of a three part series, in which Adam Wood examines the 70's British punk movement, he writes about the fashion, fanzines and sexual psychology of the movement

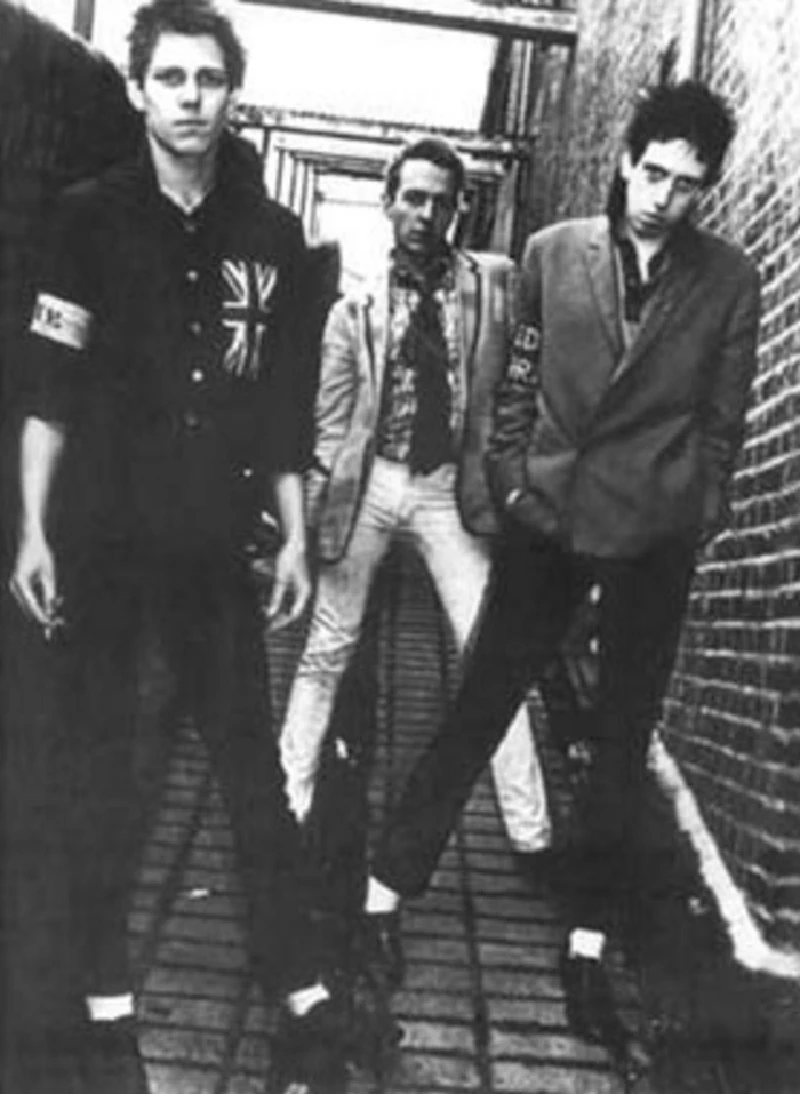

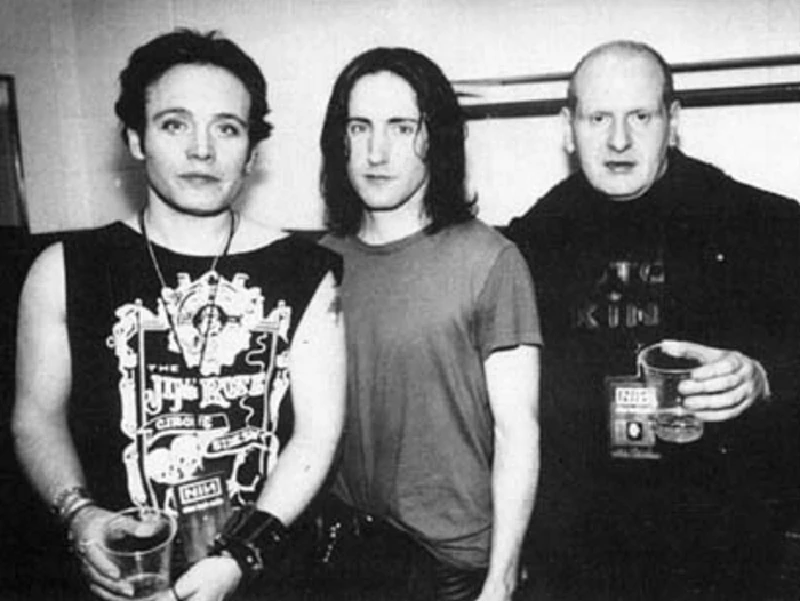

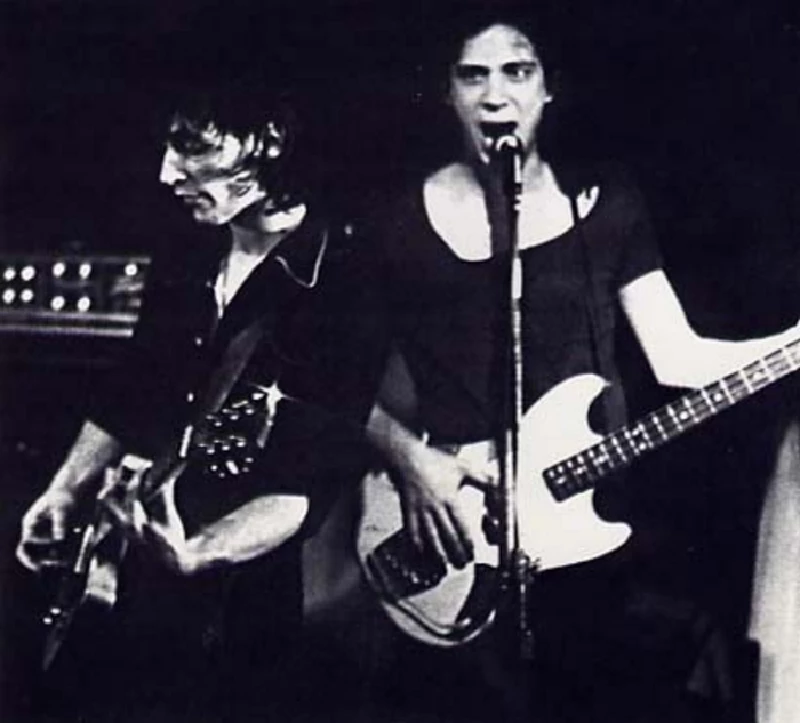

Johnny Rotten once described the punk generation as “The flowers in your dustbin.” And so they were, thrown out as a bunch onto the refuse heap of society, something pretty cast aside. But it is a kind of rejection to be revelled in; through dismissal the punks created unity, a community of their own that is forged contrary to the restrictive norms of a seemingly repressive society. This was echoed by Jon Savage who wrote: "If you were a punk, you suddenly found yourself a scapegoat, an outsider," a combination of a provocative style of dress and an apparent air of nonchalance toward conventional life helped create this disparity in British culture. Through a do-it-yourself attitude to making and distributing music, and an original style of dress, the Blank Generation were able passively resist the environment that created them. Punk fashion was designed to stand out and to provoke. Filmmaker and writer Bob Gruen recalls seeing Richard Hell in 1975 “Wearing a homemade white T-shirt with a bull’s eye painted on it, and the words 'Please Kill Me' written on it. It was one of the most shocking things I had ever seen.” This simple T-shirt helped to start punk’s ‘Resistance through Style’. It is the self-expression of art, in creating a fashion statement. As Hell in the United States felt rejected by being labelled a failure in conventional terms, so too were British youths. He declared: “I have been classified null by the society I live in.” Ed Sanders, a poet and bookstore owner in the 70's described punks as reminding him of: “Armadillos: people whose attire was a kind of armour to protect themselves from the tentacles arising from the iridium to get them.” Punk fashion was a stylistic defence mechanism from the wider world. The creation of punk allowed many to highlight if not solve the problems they saw around them. For Marco Pirroni of Adam and the Ants it was a problem of sexual equality that was solved by punk, “It was a rebellion against the lad ethic – get drunk, pull a bird, and get around the back, wherever… We didn’t want to slip back into that rock thing.” A problem of sexual equality was clearly one that was countrywide. The punk community offered a kind of sexual liberation different to that given by the contraceptive pill. It was in a sense anti-sex (though not exactly celibate), blurring the lines between genders and frankly demystifying sex. In an interview with Sounds, Sid Vicious reflected an anti-sex attitude, claiming that “I don’t believe in sex at all. People are very unsexy. I don’t enjoy that side of life… I personally look upon myself as one of the most sexless monsters ever.” This kind of attitude stemmed from both a knee jerk reaction against the norms of the rock industry (like the infamous hordes of groupies that followed major rock groups such as Led Zeppelin around the world) as well as a reaction against the trend of ‘sex sells’ in advertising. Caroline Coon agrees: “The punk movement was the first time that women played an equal role as partners in a subcultural group. Up until then there were no female equivalents to Skinheads or Teddy boys.” Punk achieved this through attitude and through style, overtly using bondage gear, PVC clothes and other fetish wear, typically sold in shops like Malcolm McLaren’s 'Sex' on the Kings Road in London. By bringing such attire into the open, the Blank Generation not only helped to demystify a darker area of sex based around male domination, it also ridiculed it. To, however, say that the punk community was a utopia, Steve Jones, the guitarist in the Sex Pistols claimed that he was only in a band “For blow jobs,” something more attributable to rock dinosaur than a punk musician. Despite the fact that Punk arose to highlight or combat contradictions, for all its seemingly good intentions it could not escape the confines of the environment from which it was born. The Blank Generation in general had a finite look, something deliberately intended to stand out and show distance from the norms of society, in the same way that Teddy Boys wore high fashion from the 1950s. Jon Savage described punks as being like "The post modern children of Dickens", a sort of street urchin look perfected by young punks Slaughter and the Dogs, who the NME described as “Grubby mid-teen delinquents spawned by a local sprawling council estate.” A key element of punk fashion was that it was designed to emphasise less desirable elements of British society often hidden from mainstream view, in this case ugliness and poverty. This ugliness and filth was intended to act as a signifier, bringing to light the parts of British life that were deliberately swept away, personifying the statistics beneath the poverty line. In Roland Barthes’ 'Mythologies', an obese wrestler named Thourin inadvertently works as a precursor to punk style, his repellent appearance is used “To signify baseness but in addition ugliness is wholly gathered into a particularly defensive quality.” Just as many punk groups capitalised on their ‘outsider’ look to achieve the desired metaphor for the poorer elements of the lower classes and again to act as a kind of fashion armour. Barthes sought to prove that all elements of society, from a haircut to a consumer durable are signifiers of meaning and exist only within a coded system of signification, that is to say the context of its intended meaning rather than a meaning posed by reality. This helps to explain the punk use of the Nazi swastika symbol. Rather than its conventional meaning, that of oppression, anti-intellectualism and ultimately genocide, from a punk point of view it comes to represent a symbol of freedom, a rebellion against a hierarchy that has given the symbol such significance. The swastika no longer represents a badge of uniformity as it had done to members of the Nazi Party. It now belongs to an avant garde style of dress belonging to a group of people who feel distanced and excluded from society. According to former music magazine editor Mark Sinker, "To present oneself as blithely unmoved by the crimes of outcasts so complete [i.e. the Nazis]…is to deny oneself the reactionary comforts of community." By re-evaluating and reusing so potent a symbol as the swastika, the wearer makes a rejectionist, cultural decision rather than a political one. Style became one of the key signifiers in punk, though it is not the only factor. The primitive simplicity of punk music is also key-As Joe Strummer said “Punk ain’t the boots or the hair dye.” When Johnny Rotten said “We’re into chaos not music,” he was not merely talking politically or denying the potential power of his music, he was emphasising the importance of the messages within punk music. The purpose of deliberately making music that was not as technically advanced as prog was several fold. It meant that punk musicians would not be accepted into the pantheon of rock giants who regarded punk music as too amateurish to be comparable to their own; why ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris refused to let the Sex Pistols onto the Old Grey Whistle Test. The lack skill allowed punk fans to concentrate on the message without being overawed by the music, in effect making the medium secondary to the message. As Mick Jones candidly said 1977, “I wanna reach the audience, I wanna communicate with them. I don’t want them to suck my guitar off.” The fanzine 'Sideburns' accelerated the spread of the D-I-Y Dadaist ethic when in December 1976 it published a picture of three guitar chords and wrote underneath “Now form a band.” A crucial part of the punk scene was the birth of the fanzine, crudely made drawings and badly typed interviews on photocopied sheets of A4, on sale at various punk gigs. The most notable fanzine was 'Sniffin’ Glue' started by Mark Perry who later went on to head the band Alternative TV. The explosion of fanzines from 1976 to 1978 made a creative outlet from which admirers of punk could express themselves. By the time the NME were starting to be positive about or even acknowledging the burgeoning punk scene, there were three and a half issues of 'Sniffin’ Glue' already in circulation. Mark Perry, the creator of 'Sniffin’ Glue' was asked as to why the magazine was named as such, to which he replied “If anything summed up the basic approach to the new music, it was the lowest form of drug taking.” As punk applied a DIY attitude to the music press, it also applied a DIY attitude to the record industry itself, adding a new dimension to the process of leisure production. As punk arose from the streets, so did independent record labels like Stiff, able to meet the demand for records that major labels were initially refusing to release. In 1976, Two-thirds of the record industry was shared between six major trans-national companies. Making it hard to break through at every level. The basic punk sound need not be achieved in a high quality studio; rather its standard drums/bass/vocal/guitar could be easily and cheaply recorded on a four-track machine in a basement. The record would then be pressed through new independent labels like Stiff and distributed in independent record shops like Rough Trade. Another example of the punk creating its own alternative to the conventions of the 1970s; a kind of resilience to the industry by adapting pre-existing ideas within the music business. The punk was able to passively reject the mainstream through its reinterpretation of signifiers that make up the common consciousness of society. Its unique style arose from the areas under the West Way pass and the tenement blocks and sink estates, deliberately taking distasteful elements of society and aligning with them in order to reject society’s preconceptions and unite as a community. Its DIY ethic spread not only to clothes but to music and publications, allowing every part of the Blank Generation to engage in an artistic and Dadaist way in order that it might find an avenue for self expression. Punk rock groups revelled in rejection, reusing it as a creative force. When Charles Shaar Murray described the Clash as “The kind of Garage band that should be speedily returned to the garage and locked in with the engine running,” the Clash responded with the gleefully vicious ‘Garageland’: “Back in the garage with my bullshit detector/Carbon monoxide making sure its effective.” The punks learnt resistance through style, through musical simplicity and most importantly by doing it themselves. Part 3 The Politics of Punk will follow next month.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Screamin' Cheetah Wheelies - Sala Apolo, Barcelona, 29/11/2023 and La Paqui, Madrid, 30/11/2023Anthony Phillips - Interview

Difford and Tilbrook - Difford and Tilbrook

Rain Parade - Interview

Oldfield Youth Club - Interview

Autumn 1904 - Interview

Shaw's Trailer Park - Interview

Cafe No. 9, Sheffield and Grass Roots Venues - Comment

Pete Berwick - ‘Too Wild to Tame’: The story of the Boyzz:

Chris Hludzik - Vinyl Stories

previous editions

Microdisney - The Clock Comes Down the StairsWorld Party - Interview

Michael Lindsay Hogg - Interview

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Ain't That Always The Way - Alan Horne After The Sound of Young Scotland 2

World Party - Interview with Karl Wallinger

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Steve Harley - Interview

Prisoners - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Marika Hackman - Big SighSerious Sam Barrett - A Drop of the Morning Dew

Rod Stewart and Jools Holland - Swing Fever

Ian M Bailey - We Live in Strange Times

Loves - True Love: The Most of The Loves

Paul McCartney and Wings - Band on the Run

Autumn 1904 - Tales of Innocence

Roberta Flack - Lost Takes

Banter - Heroes

Posey Hill - No Clear Place to Fall

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart