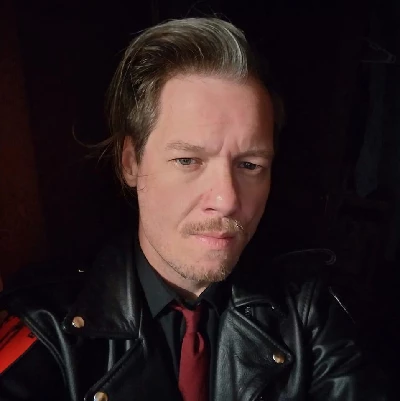

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities - Heaven Is Whenever We Can Get Together: 2 - ‘The best advice that I've gotten’

by Steve Miles

published: 3 / 7 / 2023

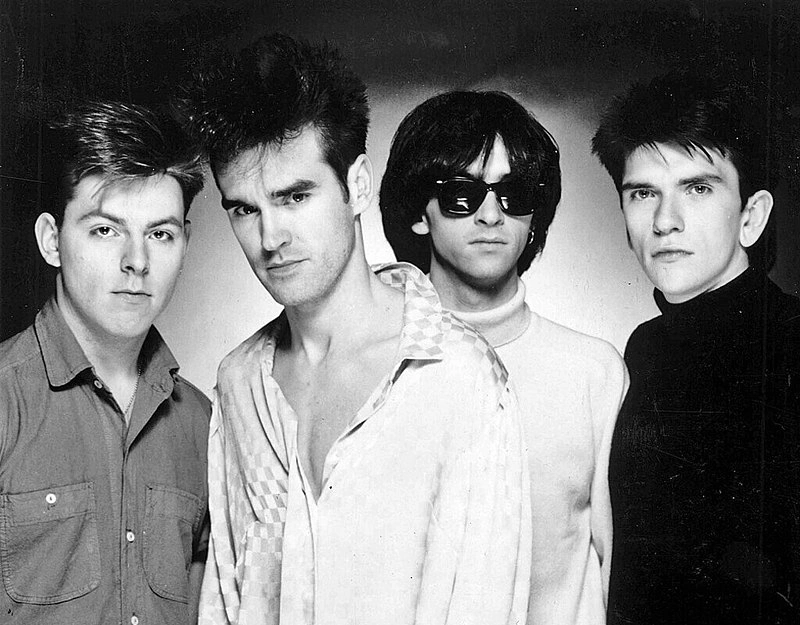

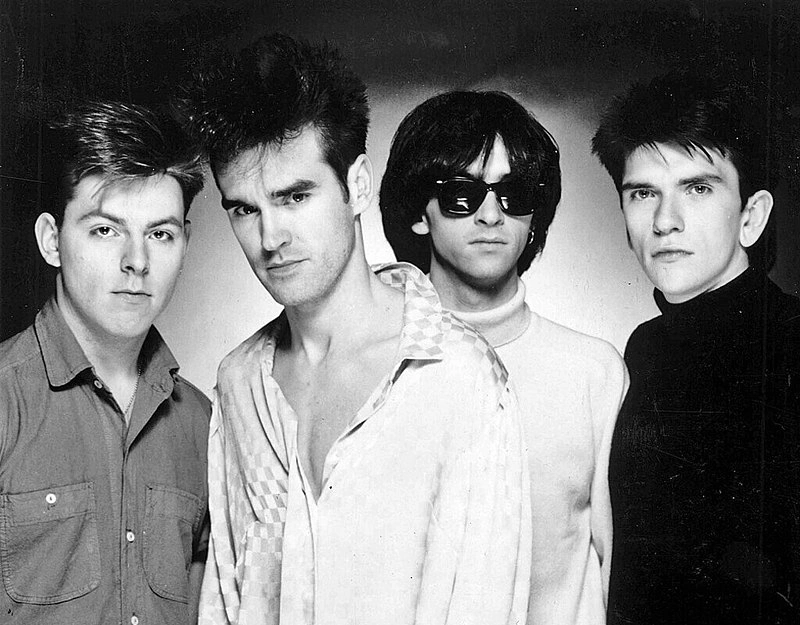

‘The best advice that I've gotten/ Was from good old Johnny Rotten’ –‘No Future’ from Craig Finn’s ‘Clear Heart Full Eyes’ (2012). In this special article spread over four parts, Steve Miles discusses the role of intimacy and belonging in music: how musicians and songwriters create a special sense of closeness with their audiences, and vice versa, whilst at the same time understanding that intimacy can sometimes elude even the tightest daily relationships. In part one we looked at the death of Ian Curtis and the way that even artists aren’t always an open book to their friends and family. We heard a lot from Craig Finn of The Hold Steady, whose ninth album, ‘The Price of Progress’ was recently released. In this second part, we explore the links between religion and fandom with Craig, and ponder gigs by The Smiths, The Libertines and The Dandy Warhols as we seek to find an answer to why we love our music so much? With religious imagery being so prevalent in Craig Finn’s lyrics (In ‘Distortions of Faith,’ for example, he can’t help referring to a plane’s take off as an ‘ascension’), and with the band’s fanbase being so devoted, I stuck my tongue firmly in my cheek and asked him if The Hold Steady were a cult? ‘We are a cult band, which is different than a cult,’ he replies curtly. But then he confesses that in fact, there are sincere similarities to him between organised religion and The Hold Steady – showing just how seriously he takes his art, and how importantly he takes his audience. ‘If you go back to the history of rock and roll, you go to Little Richard who, you know, took a lot of his stuff from the church. If you think about Springsteen or someone like that performing to a congregation, that's certainly what we do: we gather people and we, in some way, go through these paces that in some ways mirror a service. And I think that people hopefully, get out of it some of the same things, you know, like, feeling better when they walk out than when they went in.’ Few artists would dare to be that sincere about their work and their audience; they would fear seeming pompous or precious, but no-one could mistake what Craig feels for anything other than genuine love – for his work and for his listeners. And I told him that I thought what he said was wonderful, and joked that he was a hip priest - a reference he got straight away, having been schooled in UK post-punk as a young man. In fact, I was surprised to hear that Craig ‘probably knew all the words to Hex Induction Hour’ (The Fall’s fourth album, 1982) before he discovered Springsteen. ‘Yeah, that's something I certainly loved, that kind of post-punk thing. I came to classic rock a little later. I grew up with punk and hardcore and indie rock and post-punk, and then it was just getting things in order as a music fan. If you listen to Bob Dylan and go to Springsteen and Lou Reed, you can see the trajectory. That sense of discovering classic rock later was a missing puzzle piece to me. Like, one of my favourite bands is The Psychedelic Furs and all of a sudden I started paying attention to Bowie and was, ‘Oh, wait a minute...’ ‘I guess, I am sort of the hip priest. I mean, we have these youth leaders in churches, over here. Our churches are, of course, weirder. I don't want to be that guy. I think I'd rather be the hip priest. I do like a little bit of formality. So I think I'd rather be the priest than the youth group leader!’ So, how does it feel to have a congregation, I asked him, inviting him to expand on the origin of the Unified Scene? ‘Oh, yeah, it feels good. We've been reminiscing quite a bit for this 20-year anniversary. And when we started the band, we were definitely talking like we want to have a band that you feel a part of. I was really into punk and hardcore music when I was young and hardcore was very much ‘the scene’: you went to the show, even if you didn't care about that particular band. You were hardcore kids so you went to the hardcore show. And there was a real sense of a scene and a united kind of thing. Tad and I said, what if we had a rock and roll band that was a little more trad rock, but it was like that - like you felt a part of it. And I think there's some historical precedent. The Clash was one of them. And that's a band I obsess over, so I've read a lot articles about Joe Strummer pulling people into the gig through the windows and letting them sleep on his hotel floor. And as I've gotten older and researched a little more, Mott The Hoople had some of that community around them, where people really felt a part of it. And I think Mick Jones might have been a big Mott The Hoople person... So, yeah, we talked about that a lot.’ Of course, if there are cults and believers then there are also heretics. And I am one of the latter when it comes to The Clash. Everyone says that Strummer was a wonderful man, which I believe, and I'm not knocking the vim and vigour of some of their early classics, but I have to confess that I have never seen the light when it comes to Brixton’s finest. At the risk of being burned at the stake, they always seemed contrived in their politics, clumsy in their lyrics, and derivative and stodgy in their music. But Craig loves them, so please don't hold that against me and continue to read on. We must respect diversity of faith in the modern world. Craig Finn expands further: ‘That said, even though that was part of the talk before we even played a show, I'm not exactly sure how we pulled it off! I think one thing that might have helped was that we were a little older when we started the band; it was kind of a second band. I was 31 when we started, and there might have been a feeling of people kind of rooting for us. I think some part of the fan base that sort of felt it was an underdog thing and wanted to be a part of it.’ But he is also aware that the band’s daily behaviour probably matters more than their bar-room blueprint in the creation of their special fan base. ‘You know, we make ourselves somewhat available. There's a song on the new record called ‘Understudies’ and that's about someone who can't get to sleep after the show. And that's definitely me. It's not me in the song, but I very much relate to that, and one of the reasons I love the UK is that the shows are a little bit earlier so we get that extra hour of being out in the pubs and talking to people and stuff like that.’ I asked him whether it made him feel warm inside to see people arranging up to meet on social media from all over the country, or even the world, at their shows? ‘Yeah, it does. It's a beautiful thing. I think that that's some of my favourite stuff. I don't know all our fans, but I know a good handful of them.’ ‘A lot of it comes from being a rock fan. I remain a big music fan. I go to shows and I think that being treated well and building something like that is important. A lot of bands try to do it, but might be inconsistent with it, or just get tired on the road, you know. But you look at someone on a huge level, like Bruce Springsteen, who is obviously a hero of mine, and you never hear some guy talking about how Bruce Springsteen in a grocery store was a total asshole. You never hear that story. You just hear about Bruce spending just a little time making a positive impression and probably my take on it is to try to be that too. Which is not to say that, you know, I don't sometimes draw boundaries but you know, you try to do your best.’ ‘I mean, we are a cult thing. Bruce Springsteen cannot go to the pub after the show. It would just be overwhelming. Within the past year I went to - I was not going to name names, but I went out with someone who was very, way more famous one night - and he had to leave, you know? That's the other side that says what happens if you're 10 times as big as this… I think we exist in a very sweet spot, you know, and we have a small flame that burns very, very hot.’ There are a few big stars, I think, who manage to make fans feel like they know them, even though they’re huge, like Taylor Swift? ‘And Springsteen is the same way. I mean, people feel very much a part of being a Springsteen fan. Taylor Swift does a really good job of that too. But there's security and, you know, Taylor Swift CANNOT go to the pub!’ ‘The people who are into it are very into it, you know: people say we’re either your favourite band or you don't like us, and I think that's good. There aren't a huge amount of casual fans. I think you could say that my voice, or my approach to vocals, is an acquired taste. But I think once you get it - if you get into it - there's a lot there. I do try to tell stories in a way that's unique and, you know, mash them into music in a way that's probably unique. And I think again, what we're at, at twenty years is very singular.’ I can relate to that idea very clearly. As a young man, just a few years older than the teenager who interrogated New Order, I went to see The Smiths for the very first time. Most of the punk and post--punk bands had disbanded or lost their direction, and there were few new voices that spoke to me with passion and wit about the world. But I saw the England that I felt around me, and I felt the alienation that haunted my days and nights, in The Smiths. And they, like The Hold Steady, were a band you either loved or didn't like at all. There were no casual fans, and I was not a casual fan. Their first album, ‘The Smiths’ (1984) felt like the soundtrack of my soul. I thought ‘You've Got Everything Now’ was stolen from my Diaries. ‘And what a terrible mess I've made of my life/ Oh, what a mess I've made of my life/ No, I've never had a job/ Because I've never wanted one.’ ‘Still Ill’ was my whole life in a nutshell: ‘And if you must go to work tomorrow/ Well, if I were you I wouldn't bother/ For there are brighter sides to life/ And I should know because I've seen them/ But not very often.’ I played ‘Reel Around The Fountain’ to my mum and she cried. ‘It's time the tale were told/ Of how you took a child/ And you made him old’ She cried because the little boy she remembered was now someone who listened to The Smiths. Someone who, like Morrissey, believed, ‘There’s more to life than books you know/ But not much more’ (from ‘Handsome Devil’, the B-side of their first single, 1983). I’d bought that single, ‘Hand In Glove’ the day it came out, thrilled, if slightly unsettled, to see the sexual tropes of male rock band’s covers subverted by an anonymous young man's bare bum in a Warholesque duotone print. I devoured everything to do with The Smiths, but being both shy, and not really a joiner-in, I didn't go to the gig with anyone I knew. Nor, like the pure Smiths fan I was, did I intend to speak to anyone while I was there… Except for the band. They, I thought, could be my friends. The chance to see them live was so special, and my income and morale so low, that I had, with hindsight, made several very strange decisions. Firstly, I had decided not to buy a ticket to this gig I was desperate to go to. Instead, I had gone to an unpleasant example of chain of electrical retailers and bought a portable cassette recorder and some batteries. So I intended to record it, but wasn’t sure how I would get in. I arrived early enough at the gig to get in well before the sound check. I saw Morrissey from afar, looking skinny and aloof, carrying his lyrics in a plastic bag, and wearing the same tortoiseshell National Health glasses as me. He looked almost as lost as me. And then, I saw Johnny Marr, shorter and more sociable, looking approachable and somehow slightly retro. I felt I could talk to him, and I am, again, ashamed now of the encounter that transpired as I met the musicians I admired. I lied to him. I told him I couldn't afford a ticket and he put me on the guest list. It was a kindness I have never forgotten, and one that made me forgive him when, for a period later in his career, he started pulling rock-god moves on stage and collaborating with dodgy acts. Thus, I covertly taped the soundcheck, then the gig, and then the next day I returned the cassette recorder to the shop where I made up some story, pleaded poverty and naivety, and eventually persuaded a suspicious and angry store manager to give me a refund. I vividly remember my excitement at the treasure that I possessed on magnetic tape, for not only had it been a blinding gig, but the soundcheck/rehearsal had been full of songs they had not yet released, many of which the band performed instrumentally without Morrissey on stage. Among them, history disclosed, were ‘Girl Afraid, ‘Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now,’ and the punkest, most electrifying version I ever heard of ‘Barbarism Begins At Home’. But fate has a way of evening things out, and while I don't recall exactly what happened, I think the best bet is that that shoddy Tandy’s portable machine couldn't handle the sound system at the gig, because whatever I’d recorded was unlistenable, and money being what it was, I soon taped over it with something else. Several years after that, in what was for me an even bleaker emotional and musical landscape, I came across a Smiths fanzine in my erstwhile favourite indie record store. This was proper ‘unified scene’ territory, the fanzine being the solo effort of a fan so committed they had made a fanzine purely for the one band, knowing it would be bought by others like them, like me. This, I wanted to be a part of, and the next issue contained my first ever venture into journalism and my last for several decades. The gist of my piece was related to the themes of this article, as I recall. I think the point I wanted to make was that while fans of The Smiths idolised Morrissey for his outsider introspection, those same characteristics would have made him invisible to them before he joined the band. My point was that the empathy and love they had for him ought also to be focused, if at all possible, on those around them. If Steven Patrick Morrissey, in his loose-fitting jeans and NHS specs, had ambled past his adoring fans in 1980, would they even have noticed? And even if they had seen that gangly, gawky boy with his heavily-annotated copy of Elizabeth Smart’s ‘By Grand Central Station I Sat Down And Wept’, would they have said ‘Hello’? Of course not. (If they had, they would have found lines from at least dozen of his songs in the underlinings… and, watching Johnny play with a cig in his mouth, might have especially noted Smart’s line, ‘I have learned to smoke because I need something to hold on to’, except that ‘What She Said’ hadn’t been written yet…) Morrissey was one of his own fans, so to speak, as he shared the same characteristics as those who idolised him: Speaking in 1991, he said, ‘Pop music was all I ever had, and it was completely entwined with the image of the pop star. I remember feeling the person singing was actually with me and understood me and my predicament.’ But, of course, nobody he walked past BEFORE he was ‘Morrissey’ ‘understood his predicament’, which is why he needed to find that comradeship in music, and might well have remained an ardent, but lonely fan, had Johnny not knocked on his door one fateful day in May 1982. Ironically, that gig also ended earlier than planned, with Morrissey walking off and a parting V-sign from Marr for the fans who had been spitting at them, abruptly closing off ‘You’ve Got Everything Now’ - which may or may not be symbolic. There wasn't another band whose gang I really wanted to belong to until 2003, when I first saw Courtney Taylor-Taylor in real life with his foppy Mohican and briefly had a man crush. The Dandy Warhols deliberately strove to create a scene, a sense of happening, in their gigs and through their records, which took concrete form later when wealth came their way, as they built themselves the kind of Warhol Factory-esque studio-cum-club that every indie band dreams of. They even did it, of course, in their hometown of Portland, Oregon, in itself alluringly notorious on these shores for its countercultural community. Whether that's real or mythical, and whether the ‘Odditorium’ is the radical festival hub it aspired to be, I’ll almost certainly never know. And even while I looked up in awe at the impossibly cool figure of Taylor-Taylor, with his cheekbones and his confidence and his big red guitar and his twin-microphones, hoping that through my fanship a tiny bit of that cool would drop off onto me, and knowing full well it never would, I knew that the Dandy Warhols were too rich, too attractive, too sociable and too experienced for me ever to be in the same universe as them. I looked at Courtney and said to myself, I will ‘never be Bohemian Like You.’ But maybe they preferred to be the centre of the scene rather than the centre of sense, anyway. ‘Hey, there's nothing in my art/ I'd rather be cool then be smart’ - Cool As Kim Deal’ (1997). But part of what appealed to me about The Dandy Warhols, which takes some thinking about given the sense of wannabe kinship I was feeling, was that very otherwordly vibe. It was as if they came from a culture – born of places and customs - of which I knew nothing. Like a holiday romance, there was an exoticism from their very name onwards that appealed to me. ‘Heavenly scene of mind/ Or could be hell/ Maybe I'm not, yeah/ Everything I should be’ – ‘Heavenly’ (2003). Of course, every successful band has a special following. Some groups know the faithful fans that follow them from gig to gig and shout out to them at gigs – The Men They Couldn’t Hang, for example, have had the fanbase of a football team over the years, the kind that chant their beery loyalty between songs. Other bands have loyal fanbases who remain at a distance – acolytes who pore over every note and punctuation mark of their chosen heroes, but don’t engage in banter with them. Bands where fans do both, like The Hold Steady, have, like Craig and his buddies, sought to create that community through shared symbols, and common iconography. In June 2022, I saw The Libertines, another band who self-consciously cultivated their own iconography, play to a rowdy, possessive audience in Bristol. My head tried to tell me that the band had become, like so many others that have split and reformed, just a covers band of themselves, but my heart wouldn’t listen, and the pint-spilling mosh-pit camaraderie was infectious and uplifting, the songs still anthemic, and just the right side of nostalgic. ‘And all the memories of the pubs/ And the clubs and the drugs and the tubs/ We shared together/ Will stay with me forever.’ – ‘Music When the Lights Go Out’ (2004). Even people in love can find each other a mystery. For a short time when I was young I had a serious girlfriend from the Czech Republic. There was a fair bit of language barrier to be overcome between us, but there was also a magnetic attraction and a strong sense of ‘meant to be’ that made that difficulty seem like a blessing. It gave us a shared challenge; she taught me about her country, and I taught her English. In the end, it turned out that the appeal was lop-sided and, after returning home to see her family, she never came back. I got a letter soon after, in the distinctive cursive script of Eastern Europe, that justified and apologised, and I replied with studied cruelty. In time, we forgave each other, and we met again a few times later, in both Prague and England, but the spark, had it ever been there, had gone. The things that came between us were in the main the kinds of differences that come between all couples - one wants the heating turned up, the other wants it turned down; one wants to go out to eat, the other wants to stay in; but what I hadn’t expected was the culture barrier between us. Language was the most obvious thing, but each issue was readily sorted – simply learn the word for ‘milk’ or ‘scarf’ or ‘handbrake’ and you were done. But it was much less easy to fill in the gaps of shared experience that I had, until then, taken for granted. Though she knew some major American music, my entire record collection was uncharted space to her, and vice versa. She knew no sitcoms, no children’s TV, no classic BBC dramas, no English books and no catchphrases. Most of what I didn’t know about her, I didn’t know I didn’t know, and I still don’t know now. A CD of ‘Ma Vlast’ (a nationalistic Czech symphony, ironically about the real Bohemia) brought from Prague and some photos of flat snowy landscapes and stories of skiing and ice skates didn’t fill the void, and I felt that there was a large part of each other that might forever remain a mystery. As I said before, there was a genuine excitement in that at times, like travelling to another country without having to put your shoes on, and a further frisson of novelty and pleasure to feel that I had something others didn’t, a kind of ‘undiscovered country’ exhilaration that gave me a buzz. But there was a sort of loneliness in it too. And on that note we’ll pause for part three, coming soon, where we’ll continue the interview with Craig Finn of The Hold Steady, putting his writing process under the spotlight, and looking at how the focus on mental health plays a key role in the band’s bond with the audience, including some truly beautiful comments by the frontman on the power of music to heal.

Also In In Dreams Begins Responsibilities

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2022)

Band Links:-

https://greenbootsmusic.bandcamp.com.Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

intro

In the second part of this four part article Steve Miles examines the links between religion and fandom with The Hold Steady’s Craig Finn, and ponders the effect of gigs by The Smiths, The Libertines and The Dandy Warhols as he continues to find an answer to the question of why and how music matters so much.

most viewed articles

current edition

Screamin' Cheetah Wheelies - Sala Apolo, Barcelona, 29/11/2023 and La Paqui, Madrid, 30/11/2023Anthony Phillips - Interview

Difford and Tilbrook - Difford and Tilbrook

Rain Parade - Interview

Oldfield Youth Club - Interview

Autumn 1904 - Interview

Shaw's Trailer Park - Interview

Cafe No. 9, Sheffield and Grass Roots Venues - Comment

Pete Berwick - ‘Too Wild to Tame’: The story of the Boyzz:

Chris Hludzik - Vinyl Stories

previous editions

Microdisney - The Clock Comes Down the StairsHeavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

World Party - Interview

Michael Lindsay Hogg - Interview

Ain't That Always The Way - Alan Horne After The Sound of Young Scotland 2

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

Dwina Gibb - Interview

World Party - Interview with Karl Wallinger

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

most viewed reviews

current edition

Marika Hackman - Big SighSerious Sam Barrett - A Drop of the Morning Dew

Rod Stewart and Jools Holland - Swing Fever

Loves - True Love: The Most of The Loves

Ian M Bailey - We Live in Strange Times

Paul McCartney and Wings - Band on the Run

Autumn 1904 - Tales of Innocence

Banter - Heroes

Roberta Flack - Lost Takes

Posey Hill - No Clear Place to Fall

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart